The brief history of crypto interop (WIP)

The blockchain ecosystem began with a single, isolated network — Bitcoin. As more chains emerged, the need for interoperability — the ability for different blockchains to communicate and exchange value — became clear. This post takes you through the pivotal moments in the history of crypto interoperability.

This post is technical, diving deep into each solution that emerged over time and offering a glimpse of what future technologies may look like. It’s not just a factual or research post; it’s also my opinions and experience about interoperability and crypto overall.

Bitcoin

Let’s step back and remember how it all started and how this problem was created in the first place. It began with Bitcoin in 2009. Once Bitcoin was live, for the first time in human history, we had a digital, non-replicable piece of information. Fast-forward to October 2011, just after 2 years of being live - Bitcoin saw tremendous growth. In June 2011, it reached a $200M market cap (then quickly dropped to $30M). Block production became much more expensive than when it started. The network difficulty increased dramatically - what required minimal computational power in 2010 became significantly more resource-intensive by 2011, and this trend has continued exponentially.

Litecoin

The growth of Bitcoin hinted at multiple scalability issues that could arise if Bitcoin continued to grow. So, a couple of projects emerged. Welcome on stage Litecoin. Litecoin was launched in 2011 by Charlie Lee, a former Google engineer, as a “lite” version of Bitcoin. The main promise of Litecoin was that it could be faster and cheaper, with lower mining costs for miners.

Charlie Lee stated that Litecoin wasn’t meant to compete with or replace Bitcoin, but rather to act as “silver to Bitcoin’s gold.” It aimed to serve as a testing ground for innovations that could later be adopted by Bitcoin (e.g., SegWit, Lightning Network).

In short, Litecoin was created to help scale Bitcoin.

How did the crypto space look at that time? You had BTC as an asset on the Bitcoin network and LTC as an asset on the Litecoin network. These networks were sovereign, separate from each other, with different sets of miners and neither knew the other asset existed elsewhere. And a simple question arose from this situation: if I have BTC, how do I get LTC? BIG QUESTION. No answer until 2013.

But what did people do? They just used CEXes (at that time, for example, Mt. Gox). You could deposit BTC, sell it for USD, then buy LTC and withdraw it to Litecoin. Nice! Would you be surprised that people in 2025 still use this exact flow when they need to do this kind of operation? Something is definitely off, but we’ll get to that later in the post. Now, let’s get back to the first technical solution that was proposed for this problem.

Atomic Swaps

In 2013, on May 2nd at 10:35 AM, a guy named Tier Nolan hit the submit button on the BitcoinTalk forum: “Alt chains and atomic transfers.” This was the first time a trustless, secure way was proposed for swapping Litecoin with Bitcoin.

So how it worked?

Let’s say Bob has 1 BTC and Alice has 10 LTC, and they want to exchange assets.

- Bob generates some random data — a secret — and calculates

HASH(secret) - He then creates a Bitcoin P2SH transaction with a script that allows spending that UTXO if the secret is provided (it compares with the hash, as Bitcoin scripting lets you calculate the hash), or, if a specified timelock expires, Bob can spend this UTXO to get his funds back.

- Alice sees this transaction in Bitcoin, showing that Bob is willing to do an exchange with her. She copies

HASH(secret)from Bob’s step 2 transaction and creates a transaction in the Litecoin network under the same condition, except now if the secret is provided, funds will go to Bob. - Once Bob observes this, he reveals the secret by making a public transaction to spend that UTXO in Litecoin.

- As the secret becomes public, Alice uses this secret and spends the UTXO in the Bitcoin network.

As Litecoin supports almost the same Bitcoin scripting with all necessary components like comparing and calculating hashes, this worked. These scripts are also called HTLCs — Hash-Time Locked Contracts. The timelock component of this exchange is essential, as it gives each party appropriate time to act, and if they don’t act in time, parties can refund their assets. This clever idea, for the first time in human history, allowed cross-chain swaps between sovereign chains in a trustless manner. Parties don’t have to trust each other or any third party.

Lightning Network

After this idea, real-world implementations emerged. One of the greatest and most successful use cases of atomic swaps was the Lightning Network in 2015. With current terms, it’s the first and longest-running L2 on Bitcoin. The Lightning Network is an off-chain payment protocol that allows users to send and receive Bitcoin instantly, with low fees and a highly scalable architecture. It achieves this by creating payment channels — temporary smart contracts between two users that let them send funds back and forth without touching the blockchain for every transaction. Only the opening and closing of the channel are on-chain. Everything else happens off-chain. These opening and closing channel contracts are created with HTLC contracts.

Ethereum

So far, so good. We scratched the surface of the interoperability space, and now as we move forward, everything becomes way more complicated. So let’s dive in. Let’s fast forward to 2015, when Vitalik Buterin and his team launched Ethereum. The driving idea behind creating Ethereum was: if we can now have a non-replicable, verifiable piece of information, it means that this information was somehow created.

In Bitcoin, that information was limited to UTXOs and some basic scripting. What if, instead of that basic scripting, we could have a fully functional programming language? And so, Solidity and Ethereum were born. With this innovation, Ethereum created a situation where new tokens could be easily generated within Ethereum itself (ERC20s). Interoperability and Atomic Swaps were pushed to the back burner and were no longer seen as important solutions, as you could create as many tokens as possible in Ethereum — in the same chain — and then use protocols like Uniswap to exchange them within Ethereum without any interoperability issues.

Additionally, centralized exchanges (CEXes) were on the rise, so if someone needed to exchange BTC for ETH, they could still do it through CEXes. In the same way, you could deposit BTC to a CEX, trade it for USDT, then for ETH, and withdraw it back. After a few years of tremendous success with Ethereum, it became evident that Ethereum needed to be scaled again. One chain was not enough; during peak times, the blockchain was getting congested and fees were skyrocketing. For a few folks in the space, including the co-founder of Ethereum (Gavin Wood), it became clear that one chain to rule them all was not going to work. So two independent projects were built around the same time: Polkadot and Cosmos. Both had a vision to enable the launching of new chains—presumably, each chain would be specialized for a specific application or use case.

Cosmos

Cosmos introduced the idea of Hubs and Zones. You would have a single blockchain HUB that would connect all Zones. Zones are separate, application-use-case-specific blockchains. They launched a Cosmos SDK, which allows you to launch your own network, with your own validators, tokens, customization, etc. On top of this, they introduced one of the greatest interoperability solutions: IBC. The core idea is that you can have sovereign chains, but these chains have a built-in interoperability solution (IBC). With IBC, each chain is required to run a light client for the other chains it wants to connect with. Running a Light Client is necessary so you can verify that something really happened on the other chain. Alternatively, you can connect to the Hub itself and only run a Light Client for the Hub. With this design, all chains can validate the Hub and route messages through the Hub. This simplifies the topology from O(n²) (direct links between all Zones) to O(n) (Zones only connect to Hubs). The latter is a core design decision built into Polkadot. In IBC (Inter-Blockchain Communication), you do not directly specify the destination chain by name in the message, like you would with an HTTP endpoint. Instead, the destination chain is implicitly defined by the channel and port you’re using. You can find a channel that you want to use from block explorers like mapofzones.

Polkadot

Polkadot introduced the idea of Relay Chains and Parachains. It looks similar at first to Cosmos, but it’s fundamentally different. The Relay Chain is a single settlement layer. Relay Chain Validators also validate all Parachains. Parachains don’t have the same freedom that Cosmos chains have in terms of their own architecture; Parachains must fit into the same architecture. This is because Relay Chain validators have to validate the parachain. So, with this design, you have a unified security infrastructure, where all chains have the same security and all cross-chain messages are validated by Relay Chain Validators. With Polkadot, you don’t have to think about this when you launch a parachain; everything is handled by Relay Chain Validators. They validate all the messages in the ‘core chain’ and send/read messages through the same settlement layer.

Ethereum Layer 2

After these few years went by without any new innovation around interoperability, Ethereum and Solana didn’t need one. Polkadot and Cosmos introduced interoperability inside their sovereign networks; you could trade your ETH for SOL, or for BTC on CEXes. Everything was good until Ethereum L2s were introduced and gained adoption. It started in 2019 with Loopring, then in 2021 with Arbitrum and Optimism. Since then, dozens of interoperability protocols have emerged. We will walk through each of them, exploring their ideology, how they approach the problem, and of course, we will test and run them. The catalyst for these interoperability solutions was driven by the design of the Arbitrum and Optimism networks. At first, they saw tremendous growth, but their design introduced a big limitation (inconvenience): you could send your funds to Arbitrum trustlessly in a few minutes, but you had no ability to withdraw them instantly. You would send a withdrawal transaction, lock your funds for 7 days, and after that time, you could only claim your funds back in Ethereum. This was a massive problem and a huge opportunity for those who could deploy big liquidity, freeze the assets for 7 days, but give users their funds instantly, while at the same time charging them a fee. This created a big economic incentive for creating an interoperability protocol, and the first ones started emerging.

What is the CORE Problem of Interop?

As you can see from the Bitcoin and Litecoin examples, as well as the Cosmos and Polkadot designs, the core driver for interoperability solutions is solving the scalability issue, and the core problem with those solutions is: who verifies what?

At its core, interoperability is simply about sending assets from one wallet to another wallet, but across different networks. When you’re considering using a blockchain, you ask fundamental questions: What is the consensus mechanism? How many validators or miners secure it? Once you’re confident in the security model, you use the wallet and make transfers.

With cross-chain transfers, you now have two sets of these same questions - you’re operating in two different security zones. For Bitcoin and Ethereum, these zones have comparable security, but for a long-tail chain or app chain versus Bitcoin, the security models differ significantly.

On top of that, you must evaluate the transportation layer itself: what handles the cross-chain transfer, and what consensus mechanism governs it? Logically, for Bitcoin-to-Ethereum transfers, the security of that transfer should be at least as strong as Bitcoin and Ethereum’s native security, right? Unfortunately, that’s rarely the case.

Here’s the complexity: to move assets from Bitcoin to Ethereum, you’re passing through a third security zone with its own attributes. Who verifies these transactions? Who signs them? What happens if validators misbehave? These are the critical questions that make interoperability complicated.

Dozens of solutions exist trying to solve this exact problem: defining the transportation mechanism and governance process. For single chains, we understand how miners and validators work. But the same scrutiny should apply to interoperability solutions, as they effectively act as cross-chain ledgers.

This fundamental question - “Who governs the cross-chain transaction process?” - has raised billions of dollars and spawned numerous solutions. This post explores most of them, examining how each approaches this core challenge.

Diving Deep

We will be exploring each interoperability protocol through 4 lenses:

- Participants - Who are the participants in a single bridging transaction from one chain to another? What parties are involved in the finalization of the transaction?

- Flow - What does the process look like end-to-end, from the user submitting a transaction to receiving funds in the destination chain?

- Security - How is the settlement done between chains? Who and what verifies what happened in the source and destination chains?

- Extendability - How extendable is the protocol? Can new networks be added? How easy is it? Are participants permissionless?

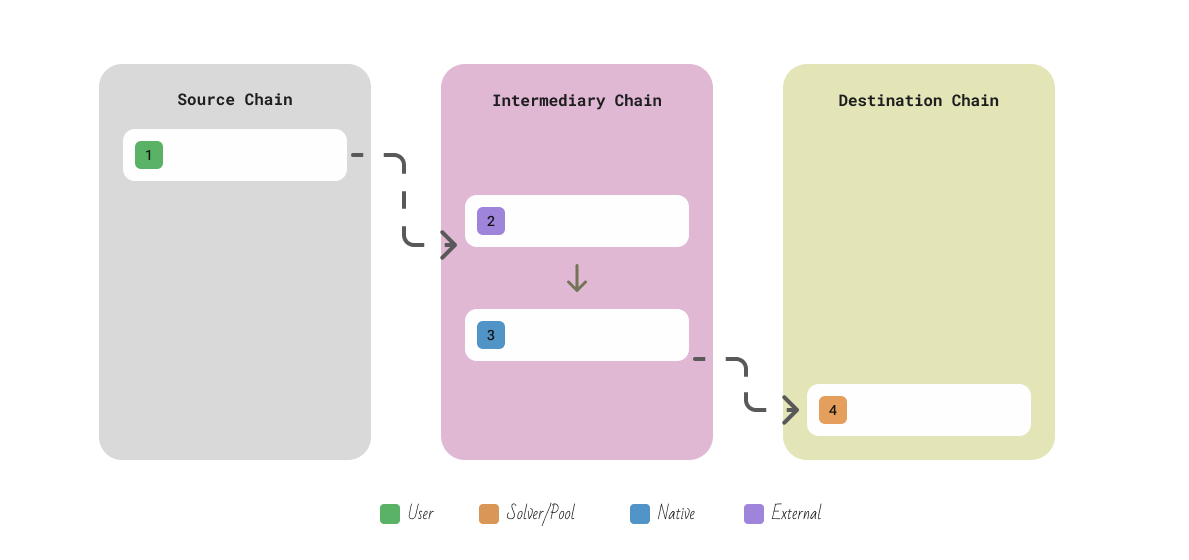

Alongside this, I will try to share my experience and some notes. I will present a flow chart to capture the basic idea of the protocol and will note with colors the actions done by specific participants or components.

- User - Person doing the cross-chain transaction

- Solver/Pool - Solver or Liquidity Pool or any participant who is front-running the liquidity

- Native - Any Native Component, Like L1->L2 bridge

- External - External component, decentralized file storage, separate network with validators, Oracles, etc.

Full list of the protocols covered in this post

- Multichain - A 21-node SMPC network that mints and burns wrapped tokens held in threshold-controlled vaults across chains.

- Wormhole - A 19-guardian validator network that signs verifiable action approvals (VAAs) to relay assets and messages between chains.

- Axelar - Cosmos-based PoS network whose validator set co-signs gateway contracts for programmable cross-chain messaging and token transfers.

- deBridge - A threshold-signature messaging and asset bridge secured by a staked validator set, with signatures permissionlessly relayed for final claim.

- ChainFlip - A native-asset AMM whose Substrate state chain and FROST-TSS vaults execute direct swaps without wrapping.

- THORChain - Bonded node network with TSS Asgard vaults and a RUNE-paired AMM that swaps native L1 assets directly.

- CCIP - Chainlink’s cross-chain protocol that moves tokens and messages via dual oracle networks and an independent risk-management guard

- Hyperbridge - Light client proof-aggregating Polkadot parachain that lets permissionless relayers deliver consensus-verified messages between any connected chain

- Stargate - A LayerZero-based bridge that taps unified liquidity pools and multi-attestation verifiers to deliver tokens.

- Everclear - A clearing layer that nets user intents and solver fills via Hyperlane, giving users instant payouts while balancing liquidity in a central hub.

- HOP - Rollup-centric bridge where bonders front hToken liquidity, AMMs swap to native assets, and the canonical bridges provide settlement.

- Connext V2 Protocol - A liquidity-network bridge that uses hashed-timelock atomic swaps and permissionless routers for fast, trust-minimized transfers across chains.

- Across - An optimistic bridge where relayers front funds instantly and UMA’s oracle later settles.

- Synapse - Optimistic bridge where collateral-posted relayers fulfill transfers immediately and guards can dispute within a challenge window.

- Meson - An atomic-Swap HTLC network allowing LPs to match stable-coin transfers between any chains with no validators and 3rd parties

- 1inch Fusion+ - Dutch-auction HTLC swaps filled by staked resolvers who atomically lock and release funds on both chains.

- Garden Finance - Intent-based HTLC network where staked solvers compete to fill swaps and face slashing if they fail to execute correctly.

- TRAIN Protocol - A permissionless cross-chain swaps protocol that uses atomic PreHTLC escrows and competitive solver auctions to enable trustless (trust-minimized) asset swaps between chains

- Centralized Bridges (Layerswap, Relay, Orbiter) - A single trusted party (the solver) receives user funds on the source chain and transfers equivalent assets from its own inventory on the destination chain.

- CCTP - Circle’s burn-and-mint bridge that lets native USDC move across chains by burning on the source chain and minting on the destination.

- LayerZero - Modular messaging layer that uses configurable decentralized verifier networks plus executors to deliver payloads.

- Hyperlane - “Choose-your-own-security” mailboxes where each app picks its interchain security module—multisig, staking, ZK, or custom—for permissionless messaging.

Multichain

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

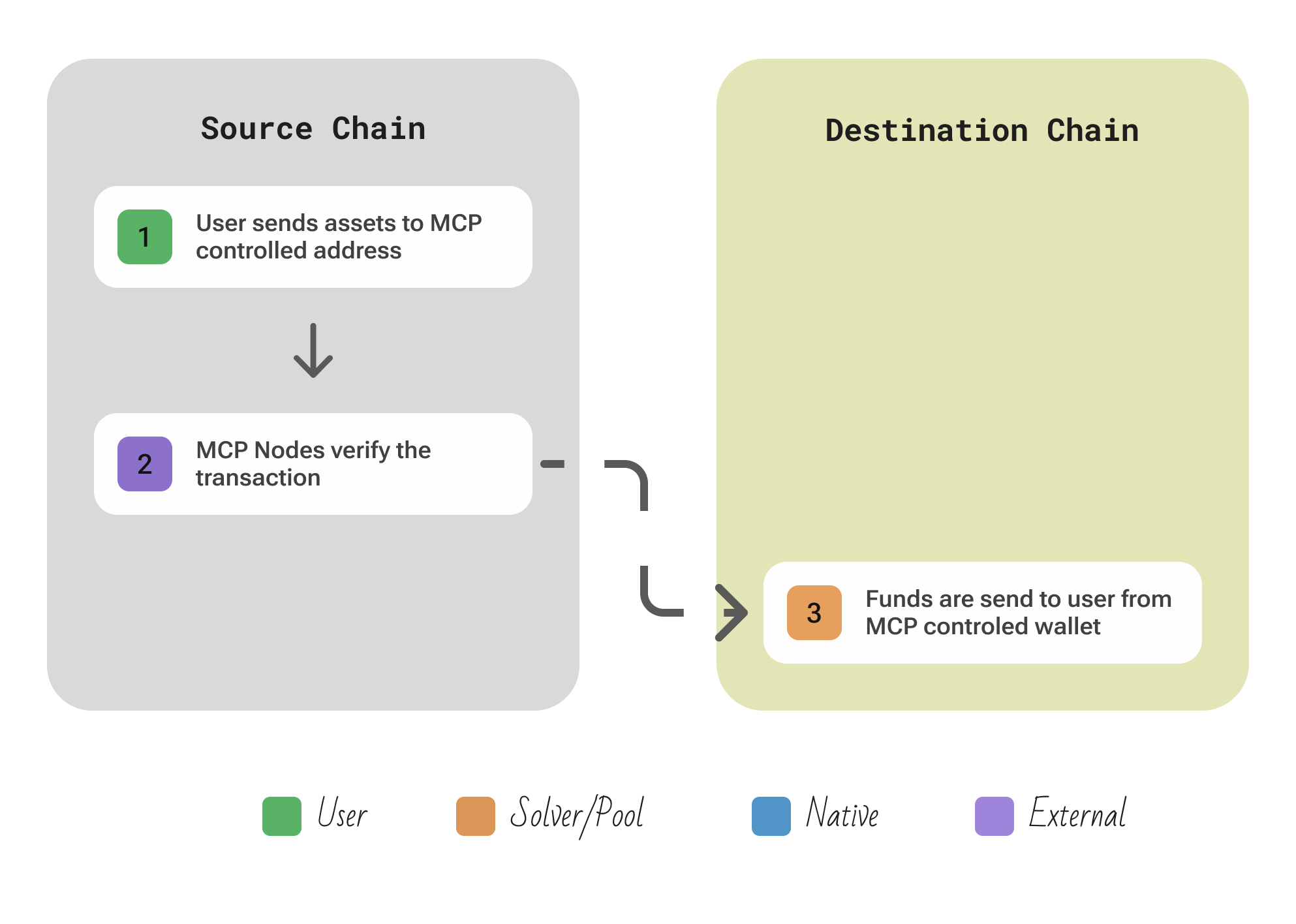

A 21-node SMPC network that mints and burns wrapped tokens held in threshold-controlled vaults across chains.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; network of 21 SMPC nodes that collectively control threshold-signature vaults holding the bridged assets |

| Flow | User deposits a native asset into the vault contract on the source chain → SMPC nodes detect the deposit and mint an equivalent wrapped token to the user on the destination chain (lock-and-mint). Conversely, burning the wrapped token on the destination triggers SMPC nodes to release the original asset from the vault back on the source chain. |

| Security | Assets are secured by a threshold signature scheme: only if a quorum (e.g. 15 of 21 nodes) colludes can the vault key be reconstructed. Nodes independently verify source-chain events and sign off-chain, producing a single on-chain signature when the threshold is met. Finality of each chain is respected before mint/release. |

| Extendability | To add a chain, the bridge contract is deployed on that chain and all the existing SMPC nodes run a light client for it. |

On paper, Multichain was fairly decentralized, even more decentralized than all current interop protocols. 21 independent Nodes, if you wanted to do something bad with this design, you would need to CORRUPT 15 nodes. Sounds secure and highly non possible right? Right. Apparently, the CEO was arrested and the whole protocol’s operations were stopped. We at Layerswap also lost around 40 ETH in Multichain. We used them for a few routes for liquidity rebalancing and their operations were stopped, but their website was running. So we just did the transaction and it is stuck forever.

The Multichain case is a good reminder that any design that relies on a closed set of a few actors is inherently critical. And strangely enough, the multisigs were not that decentralized, but their website is still up and running without any notice that the protocol is halted. Sorry for the hatred here, but losing 40 ETH at your early-stage company leaves its marks.

Wormhole

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

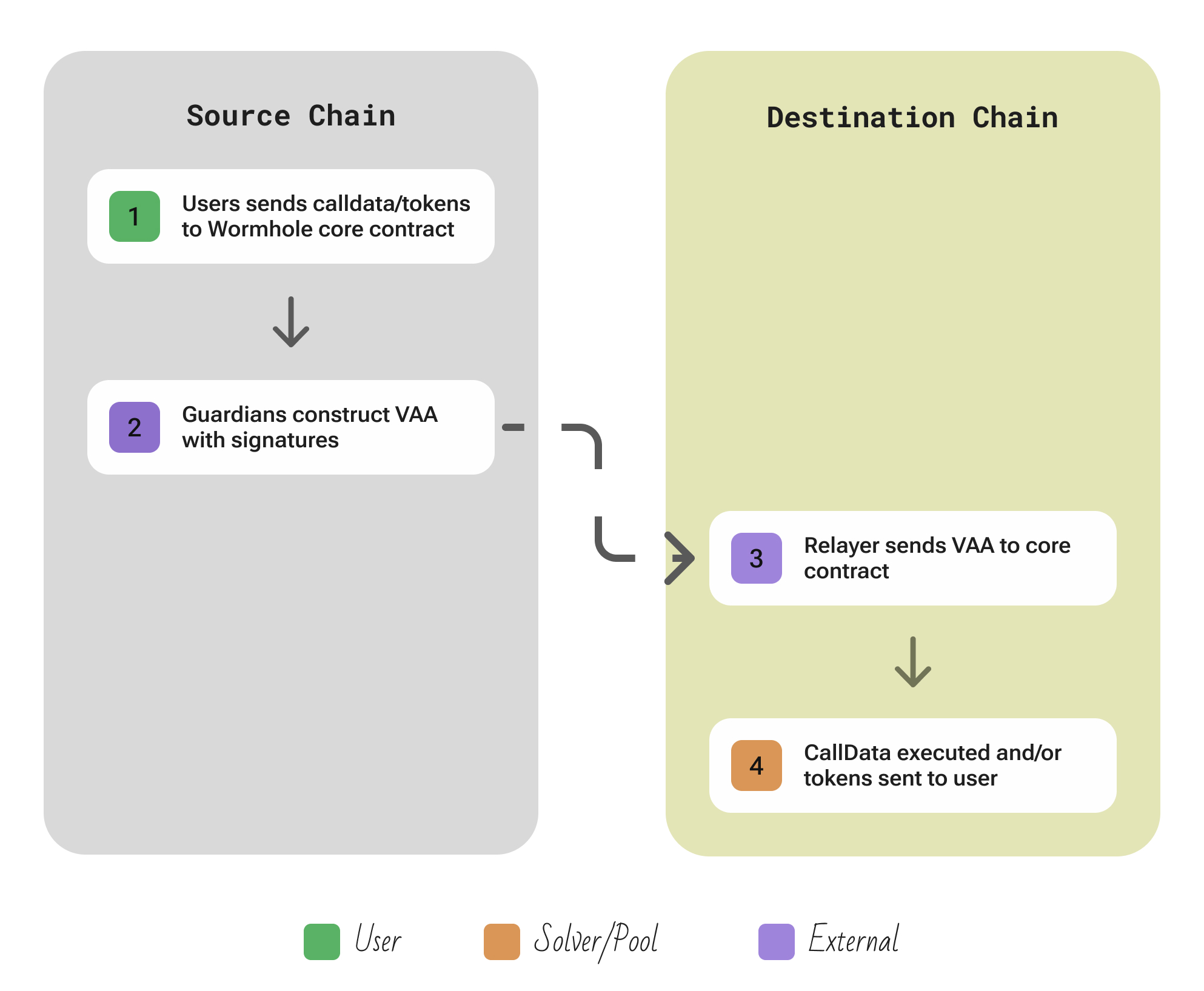

A 19-guardian validator network that signs verifiable action approvals (VAAs) to relay assets and messages between chains.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; Guardian Network - 19 independent validator nodes that sign messages (VAAs); Any Relayer carry a VAA to target chain. |

| Flow | User emits a message (or token deposit) via the core contract on the source chain → Guardians observe and produce a VAA → Relayer submits the VAA to the destination contract, which verifies signatures and mints/unlocks the asset or executes the payload for the user. |

| Security | Message executes only if the destination contract sees a valid threshold Guardian multisig; An attacker must corrupt a strong majority of Guardians. |

| Extendability | Supporting a new chain involves deploying Wormhole’s contracts on that chain and having all guardians run a light node (or adapter) for it. |

Verified Action Approvals (VAAs) are Wormhole’s core messaging primitive. They are packets of cross-chain data emitted whenever a cross-chain application contract interacts with the Core Contract.

Wormhole is one of the longest-running x-messaging protocols. They sustained a horrible $300M hack and are one of the dominant players in the space.

Axelar

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

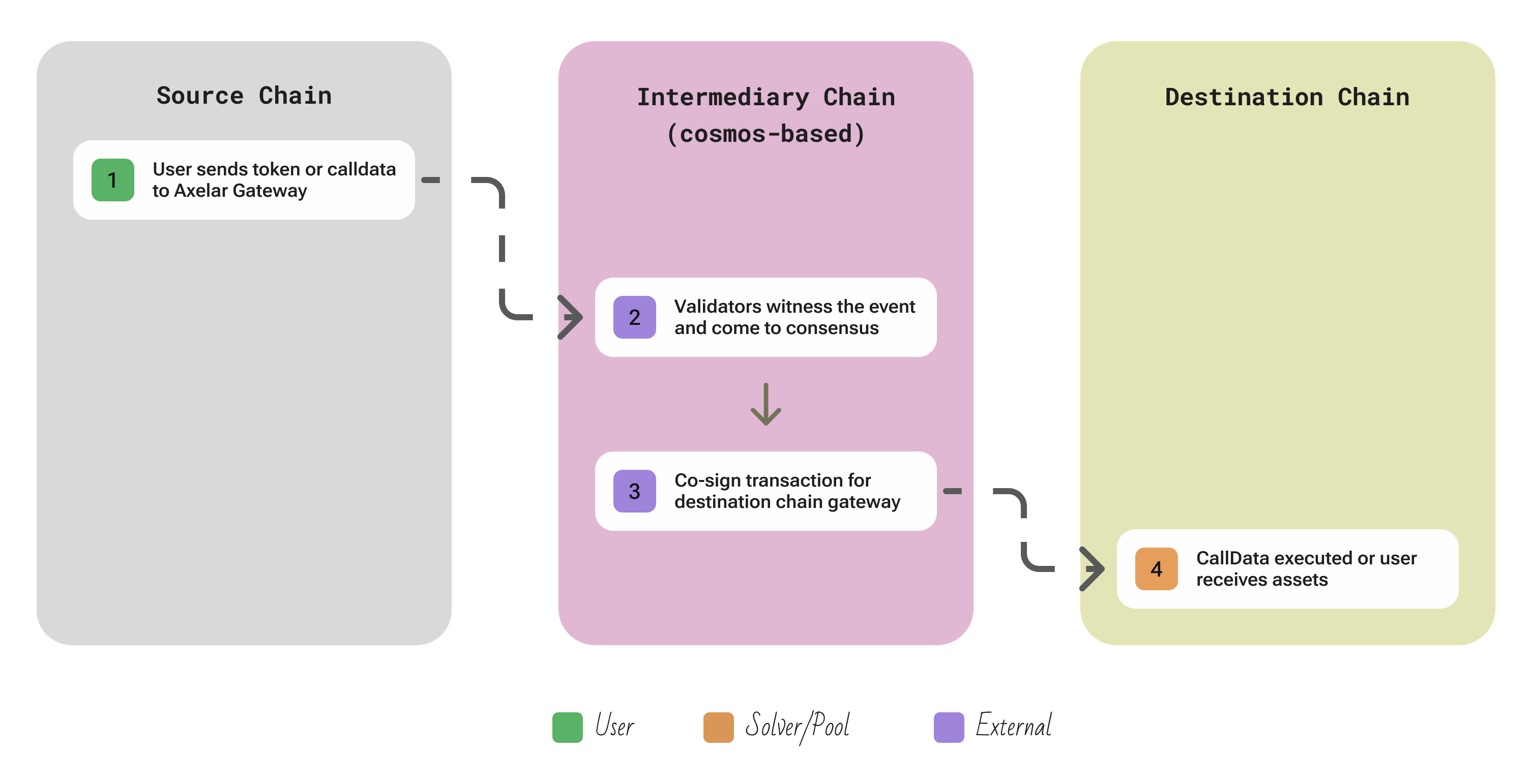

Cosmos-based PoS network whose validator set co-signs gateway contracts for programmable cross-chain messaging and token transfers.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; proof-of-stake validators that run the Cosmos-based Axelar network; Any Executor carry the co-signed message to target chain. |

| Flow | User calls an Axelar Gateway contract on the source chain (either to transfer tokens or invoke a general message) → Axelar’s validators observe the event on-chain, reach BFT consensus on it, and collectively sign an approval for the cross-chain transfer → an executor (anyone) forwards this signed approval (often as a transaction proof) to the Gateway contract on the destination chain → the destination Gateway then unlocks or mints tokens for the user (for asset transfers) or calls the target contract with the message (for generic calls) |

| Security | A cross-chain operation is finalized only after a threshold of Axelar validators (weighted by stake) sign the approval. All validators are economically staked, and any invalid signing can be punished by slashing. Because Axelar validators run their own consensus (like any Cosmos chain), the security is similar to other PoS networks – it’s as secure as the total stake (AXL token) and the honesty of 2/3 of the validators |

| Extendability | Any chain that can support a simple Gateway smart contract (EVM, Cosmos SDK, etc.) can be added to Axelar. All validators install a light-client module for the new chain and begin tracking its consensus. Alternatively, chains can use the Amplifier sub-network so core validators don’t all need to verify every chain. |

With this design, as with Wormhole, adding a new chain is a big problem because all of your existing validators should run a light client for the new chain. So with each chain added to Axelar, every Axelar node operator becomes harder and more resource-expensive to run. Axelar actually addresses this problem with the Axelar Amplifier network, where you can add a network that core validators don’t need to verify. You add a network with its own verifiers. But I am not quite sure how the security of the messages coming from verifiers is adapted and matched with messages that are verified with ‘core’ validators.

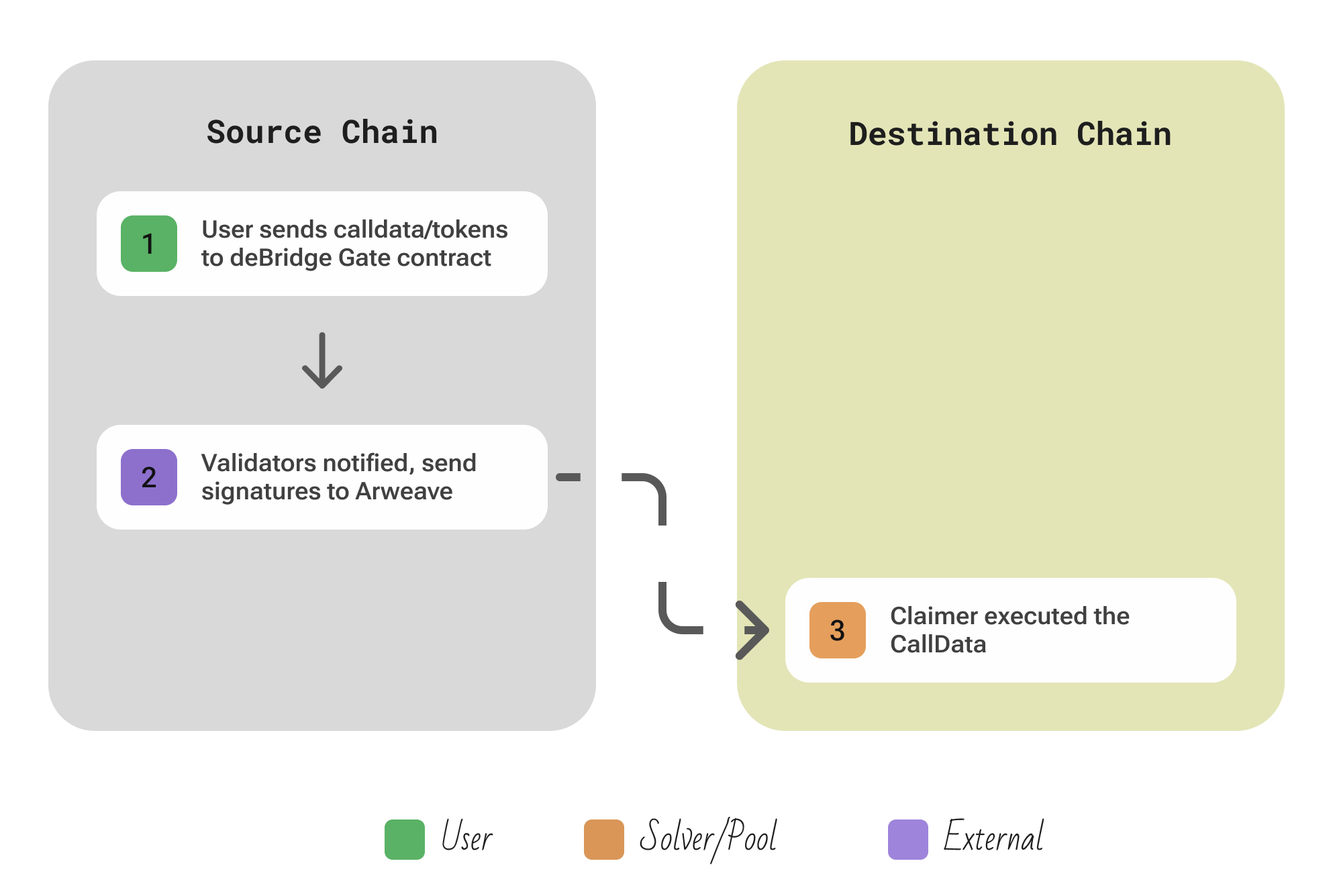

deBridge

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

A threshold-signature messaging and asset bridge secured by a staked validator set, with signatures permissionlessly relayed for final claim.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User, a staked Validator network where a ≥2/3 majority must sign each message; open Claimer submit the validator signatures to the destination chain |

| Flow | User invokes a transfer or message via the deBridgeGate contract on the source chain (e.g. calling send()) → this emits a Submission event → all deBridge validators observe the event; once the source transaction is final, they each sign a cryptographic attestation for it → these signatures (or a threshold aggregate) are stored on a decentralized layer (e.g. Arweave) → a Claimer then retrieves the signature bundle and submits it to the deBridgeGate on the destination chain → the contract verifies the threshold signatures and, if valid, releases the bridged assets or executes the cross-chain call for the user. |

| Security | The destination action requires a valid TSS multi-signature from the deBridge validator set – if fewer than the threshold (e.g. 2/3) sign, the claim is rejected. Validators are all staked, so any malicious signing can be slashed by governance. |

| Extendability | deBridge is chain-agnostic. To support a new chain, the deBridgeGate contracts are deployed there and that chain’s ID is added to the validator node software configuration. Validators must run full or light nodes for each supported chain, but adding chains is routine as long as they can parse finality and signatures |

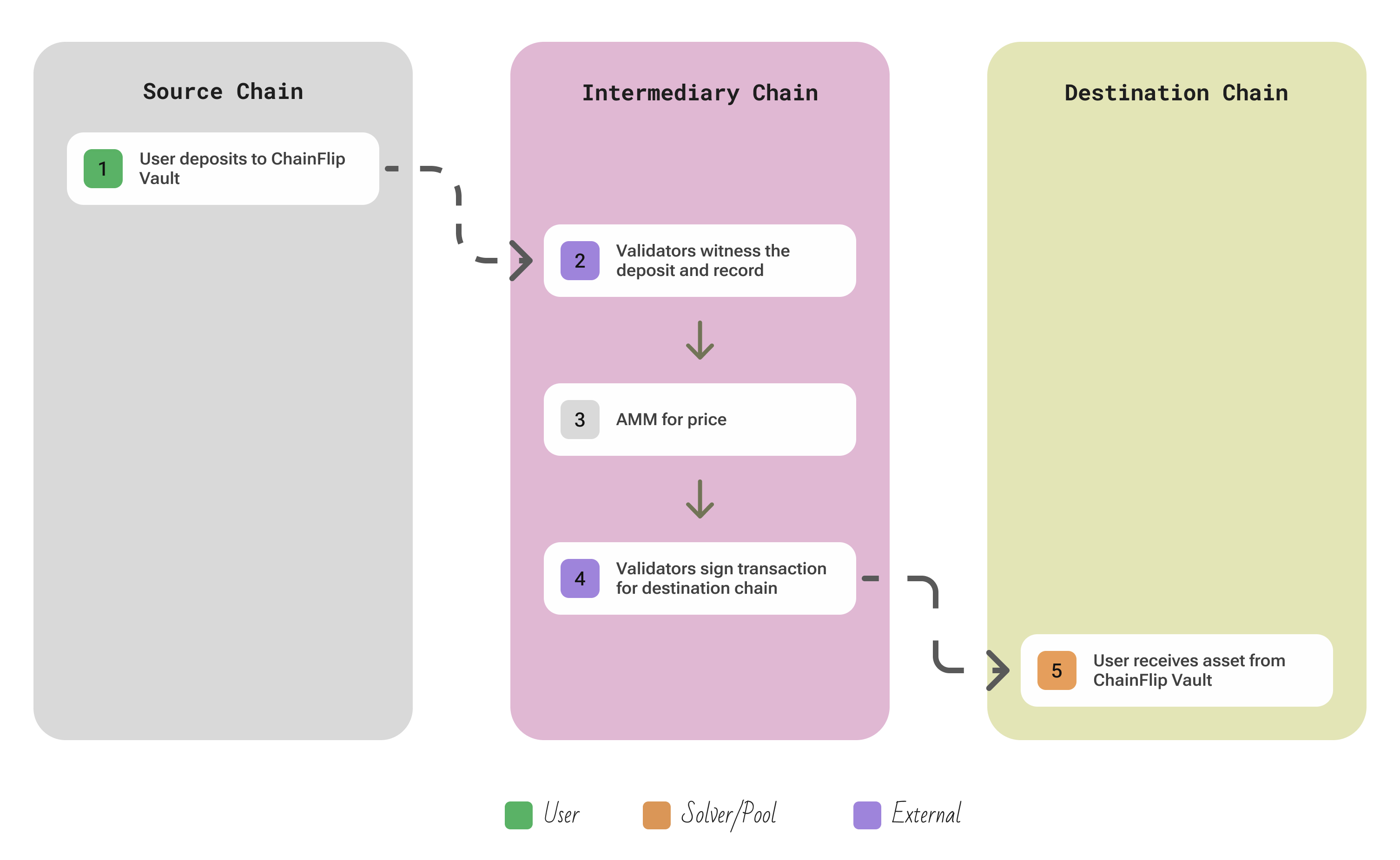

ChainFlip

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

A native-asset AMM whose Substrate state chain and FROST-TSS vaults execute direct swaps without wrapping.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; 150 FLIP-staked Validators run Substrate State-Chain; AMM Liquidity Providers who fund pools on the state chain |

| Flow | User specifies a direct swap (e.g. BTC → ETH) and deposits the input asset into ChainFlip’s Vault address on the source chain → the validators (nodes) monitoring that Vault see the deposit (once it reaches finality on the source chain) and record this event and swap details on the State Chain (which acts as an order book and pricing engine) → within the State Chain’s AMM, the trade is matched – the protocol determines the output amount using its cross-chain AMM pools → the validators collectively TSS-sign a transaction from the destination chain’s Vault to the user’s address, paying out the desired asset on the destination chain |

| Security | All user funds sit in on-chain Vaults controlled by the validator network’s threshold keys. No single validator can move funds; a supermajority (e.g. 2/3) must cooperate to sign any outbound transfer. Validators are required to put up a large FLIP token bond, which can be slashed for misbehavior, making attacks economically unattractive. The system relies on its own consensus (Substrate/Tendermint) to coordinate swaps, and validators must run full nodes on every connected chain to independently verify deposits and block finality before signing outputs. |

| Extendability | ChainFlip supports both EVM chains and non-EVM chains (Bitcoin, Solana, Polkadot, etc.) by implementing Vault “adapters” for each. To add a new chain, validators need to run a node for that chain and a vault address is generated for it. |

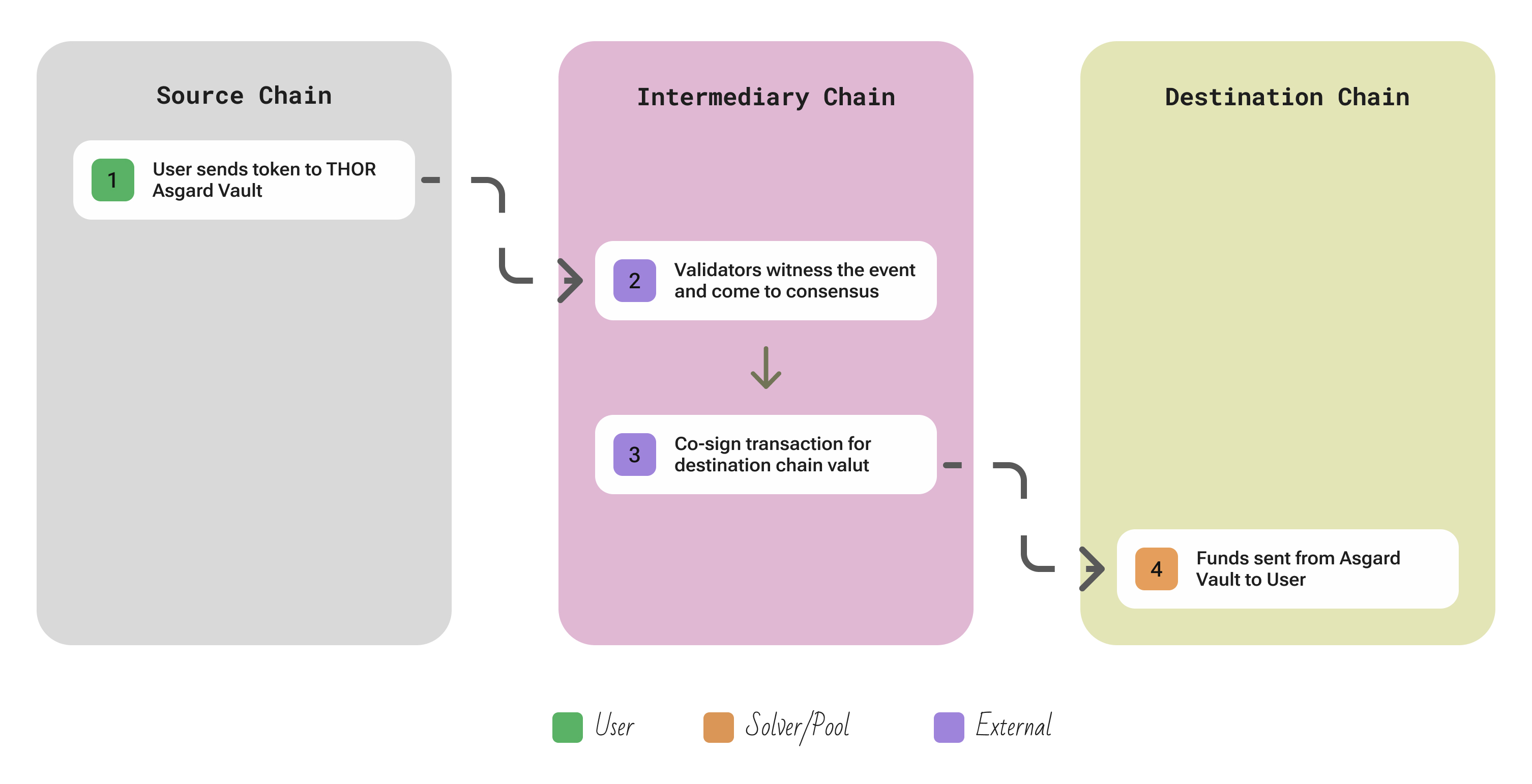

THORChain

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

Bonded node network with TSS Asgard vaults and a RUNE-paired AMM that swaps native L1 assets directly.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; ~100 Validator Nodes running a Cosmos-SDK chain; they collectively control Asgard TSS vaults; external Liquidity Providers fund RUNE-paired pools. |

| Flow | The user sends a native asset to THORChain’s vault address with a memo indicating the desired swap → THORChain nodes (called THORNodes) monitoring that address see the incoming deposit once it reaches sufficient confirmations → When a supermajority of nodes observes the deposit, they assign it to a swap transaction in THORChain’s internal ledger and determine the output via THORChain’s AMM pricing (all swaps go through RUNE pools, so BTC -> ETH swap is executed as BTC->RUNE->ETH using pool prices) → the network then prepares an outbound transaction: the nodes collectively generate a signature (using a GG20 threshold scheme) to spend from the relevant outbound vault (e.g. the Asgard vault on Ethereum) to the user’s target address. |

| Security | THORChain’s security relies on a large bonded validator set and threshold cryptography. The vaults (called Asgard vaults) are controlled by a 2/3 threshold signature – for instance, if there are 100 nodes, any 67 can sign to move funds. No single node has the private key; it’s collectively generated and stored in pieces by the nodes. |

| Extendability | New L1 chains can be added via governance. To integrate a chain, THORChain requires implementing a Bifrost client module for that chain’s API and having all validator nodes run a full node for it. |

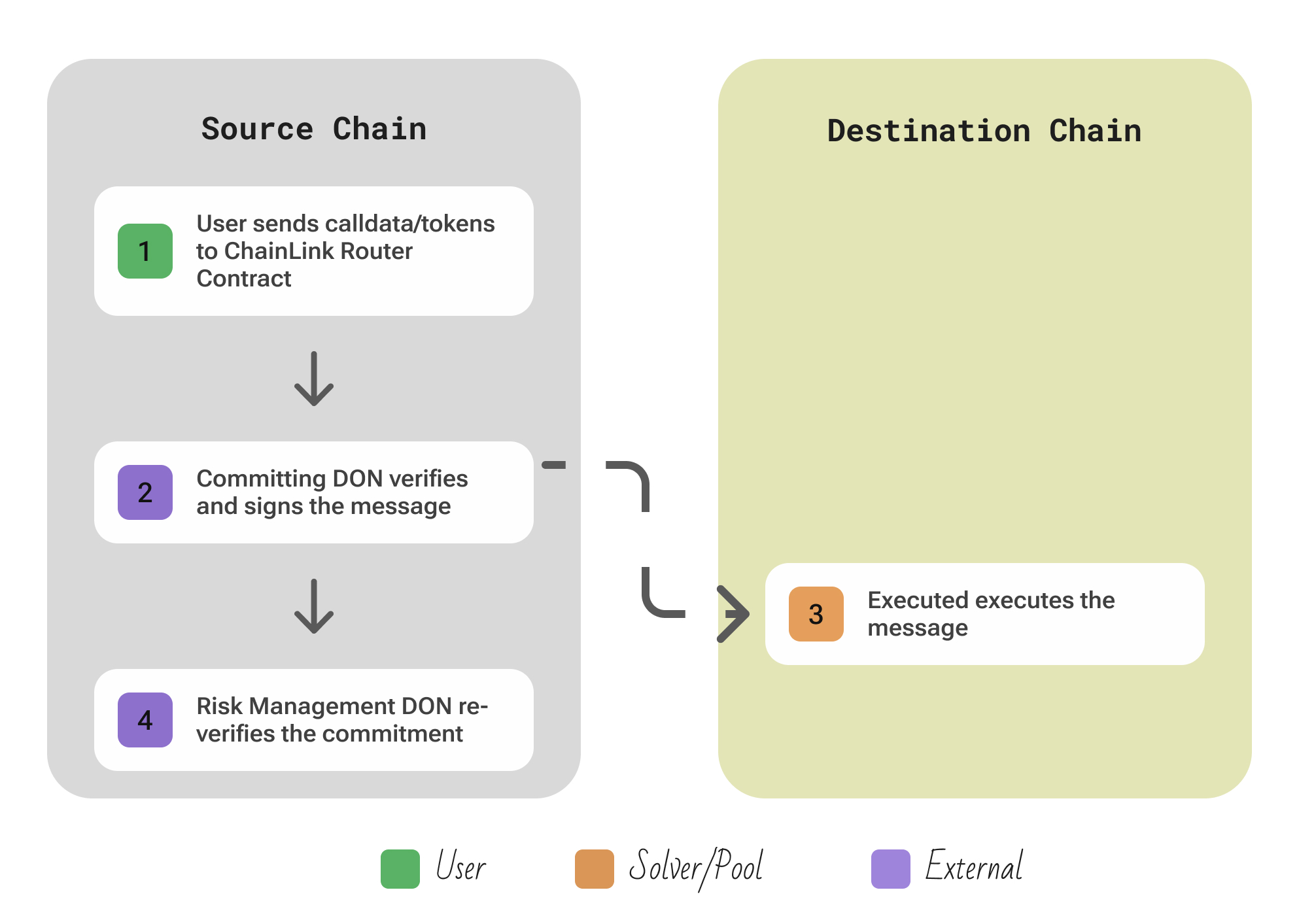

CCIP

Chainlink’s cross-chain protocol that moves tokens and messages via dual oracle networks and an independent risk-management guard.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; staked Committing DON (Chainlink oracle nodes that sign every cross-chain message), independent Risk-Management DON that re-verifies each commit; any Executor submits the attested payload and pays gas on the destination chain. |

| Flow | The user calls ccipSend on the Router contract of the source chain, providing either tokens or an arbitrary payload for messaging → The Committing DON (Decentralized Oracle Network) monitoring that Router sees the event → Once finality is assured on the source chain, the DON reaches consensus on the message details and writes a cryptographic attestation to a special contract on the destination chain called the “Commit store”. Simultaneously, the Risk Management DON is monitoring all transfers → if the transfer exceeds certain preset limits (volume, rate, destination, etc.), the Risk DON can trigger a hold or “circuit break” on the transfer before it completes → once the required number of oracle signatures from the Committing DON are posted on the destination an Executor (which could be one of the DON’s nodes or any user) calls ccipReceive on the destination Router. |

| Security | CCIP employs what Chainlink calls “Level-5” security, the highest level of cross-chain security classification. This means multiple independent safeguards: (1) The primary DON (Committing DON) is decentralized and economically secured by staking – compromising it requires bribing or hacking a large fraction of nodes which hold significant LINK stakes (similar to Chainlink price feeds which have proven robust). The Risk Management DON runs on a separate codebase and separate infrastructure, ensuring that even if the primary DON was subverted, the risk DON could catch anomalous activity (kind of like a checks-and-balances system). This Risk DON can automatically halt transfers that look suspicious (amounts beyond set thresholds, etc.), providing an emergency brake. |

| Extendability | Any chain that can host the Router contracts can integrate; Chainlink nodes just add a light-client module, so new L1s/L2s join without changes to existing networks. The v1.5 CCT (Cross-Chain Token) standard and Token Manager let issuers plug tokens into CCIP with minimal code, while dApps choose their own Executors/DON sets. |

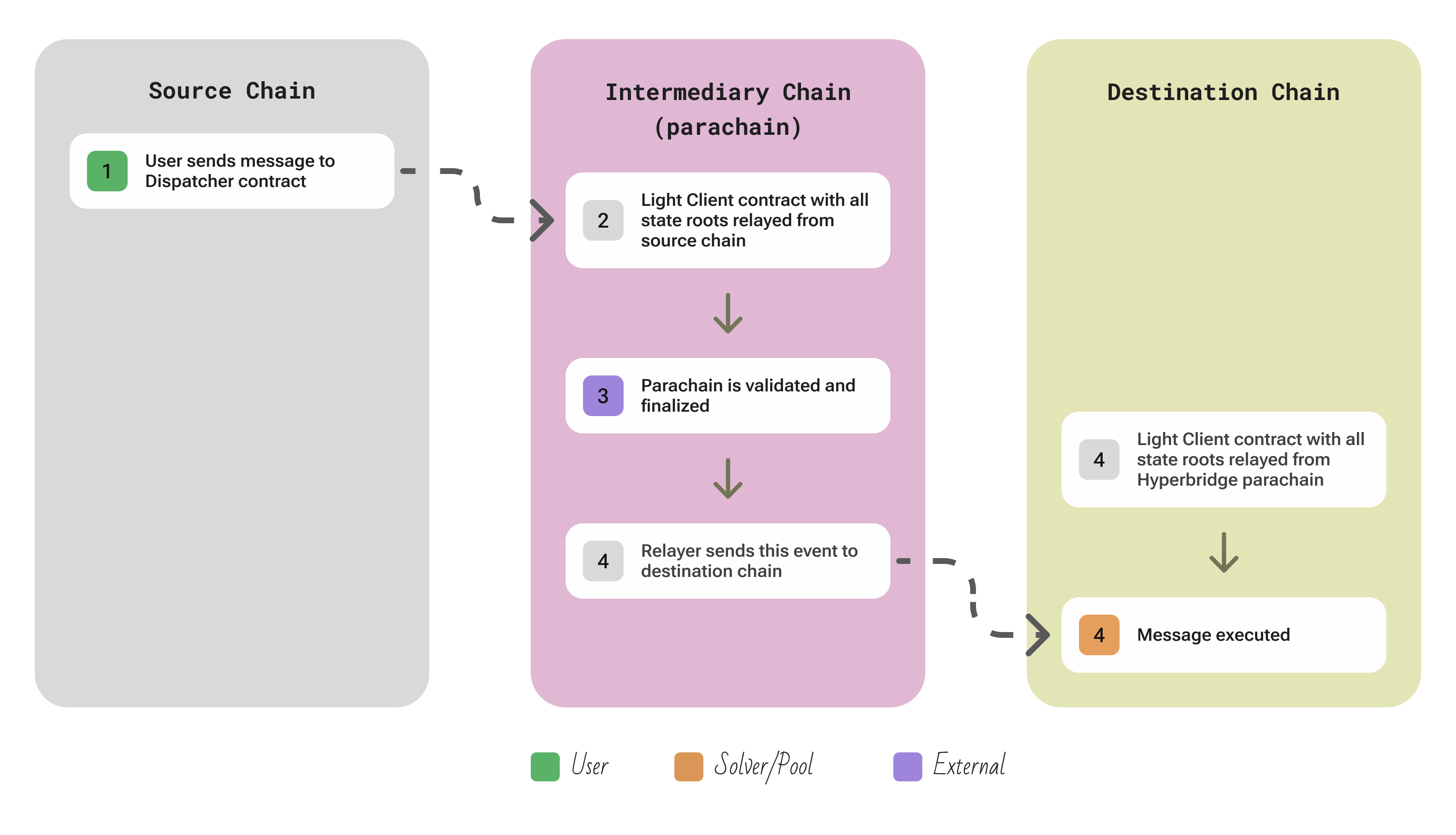

Hyperbridge

Light client proof-aggregating Polkadot parachain that lets permissionless relayers deliver consensus-verified messages between any connected chain.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; the Hyperbridge parachain (running in Polkadot) which serves as an aggregation and verification hub; permissionless Relayers (called Tesseract relayers) who fetch proofs from the parachain and submit them to destination chains. |

| Flow | The user’s contract calls the ISMP send function (e.g. dispatch) on the Dispatcher contract on the source chain, providing the payload and destination chain ID. This Dispatcher creates a commitment of the message and sends it to the Polkadot Hyperbridge parachain (this step is trustless because the parachain itself continuously reads these commitments via light clients). Concretely, each connected chain has a light client module running inside Hyperbridge that can verify that the Dispatcher emitted a given event. The Hyperbridge parachain collects all such events from all chains and includes them in its own block as an aggregated state root. Now for delivery: a relayer (Tesseract) picks up the fact that “Chain A has message X for Chain B” by querying the Hyperbridge parachain’s state. The relayer then constructs a proof that the message was included in Hyperbridge’s latest block (essentially a Merkle proof to the aggregated root, combined with proofs that the root includes the origin chain’s state). The relayer submits this proof to the ISMP Host contract on the destination chain. The Host contract knows how to verify proofs coming from Hyperbridge (it has a light client for the Polkadot Relay Chain/Hyperbridge parachain). It checks that the proof is valid and that the message was indeed committed by the source chain’s dispatcher. If everything checks out, the Host contract then calls the target function on the destination chain (previously registered) to deliver the message (e.g. unlock tokens or call a cross-chain function). This entire flow involves no privileged relayer – if one relayer doesn’t deliver, another can – and no intermediary tokens (it can be used for both messages and token movements via proofs). |

| Security | Hyperbridge relies on cryptographic verification of consensus rather than multisigs. The Hyperbridge parachain, running under Polkadot’s shared security, is responsible for verifying the state and consensus of each connected external chain (via light-client modules for Tendermint, Ethereum, Bitcoin, etc.). This means when it includes a message from Chain A, that message has been proven to the Polkadot validators as a valid event from a finalized block of Chain A. Similarly, when the destination chain’s Host contract gets a proof, it verifies the Polkadot parachain’s consensus (using Polkadot’s GRANDPA or Beefy consensus proofs) and the state inclusion. So trust is placed in Polkadot’s validators (highly decentralized and economically secure) and the correctness of the light client implementations – not in a few bridge nodes. |

| Extendability | Hyperbridge is chain-agnostic by design – to connect a new chain, one needs to implement a light client for that chain’s consensus and state proofs in the ISMP framework and deploy a Host/Dispatcher on that chain. Because Polkadot parachains have limited throughput, Hyperbridge’s design is optimized to aggregate and scale: it doesn’t require every node to track every chain, just the parachain to run clients and produce succinct proofs. Relayers are fully permissionless; anyone can run a “Tesseract” relayer and there’s an incentive model (they get fees for delivered messages, potentially enforced by the protocol) |

This bridge design has an interesting caveat. Contrary to different validator-based bridging, validators/relayers of this network do not need to run a full node / light client for any supported chain. Those runners are separate permissionless parties. Validators just have to create a light client contract and wait for relayers to fill in the data. This is a nice improvement in terms of scalability, but it comes with a trade-off.

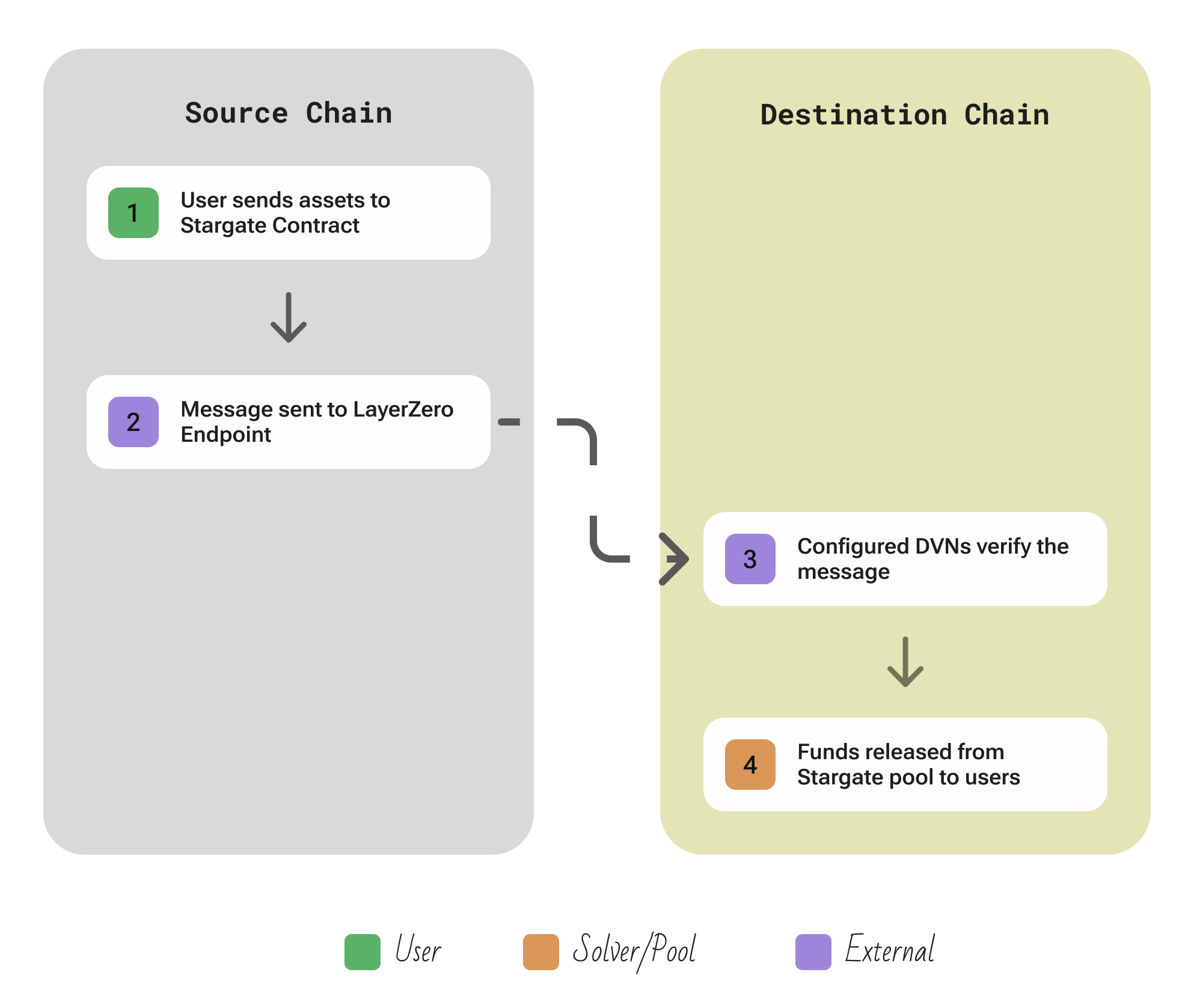

Stargate

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

A LayerZero-based bridge that taps unified liquidity pools and multi-attestation verifiers to deliver tokens

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; LayerZero Relayer; DVNs deliver source chain information; Liquidity Providers supply capital to Stargate’s pools which back the transfers on each chain |

| Flow | User calls swap() on the Stargate Router on the source chain, specifying a token and target chain → contract then locks or burns the user’s tokens into the local pool and emits a message to LZ → LayerZero’s Oracle (DVN) then delivers the source chain’s block header and transaction proof to the destination chain, while the Relayer submits the message payload and proof to the destination → the destination contract, upon seeing matching data from both the oracle and relayer, deducts the appropriate tokens from its local liquidity pool and credits the user with the native asset on that chain |

| Security | The cross-chain swap executes only if two independent parties (the oracle/DVN network and the relayer service) both attest to the same message. Neither alone can finalize a transfer. Thus, an attacker must compromise both the oracle(s) and relayer simultaneously to falsify a message. |

| Extendability | Any chain that LayerZero supports (i.e. where a LayerZero Endpoint can be deployed) can host Stargate. Integrating a new chain means deploying the Stargate Router and Pool contracts on that chain and having an oracle feed (a light client) for that chain’s headers. Because liquidity is unified — Stargate pools on different chains are all connected — adding a chain shares liquidity with all others (no siloed pools per pair). New chains do not dilute security, because the same oracle/relayers are required to add that route. |

Stargate has one of the deepest liquidities in the interop space. Works really neat and stable. They use 2 configured DVNs basically just 2 entity multisig, which I am not a fan of and the technical challenge here is if they ramp up the security, let’s say increase it to 4-8-12 DVNs the costs of the transaction would be skyrocketing and they will not be competitive in the market, considering that solutions like Layerswap and Relay, with a centralized (non-security) approach are just attracting users - until something bad happens.

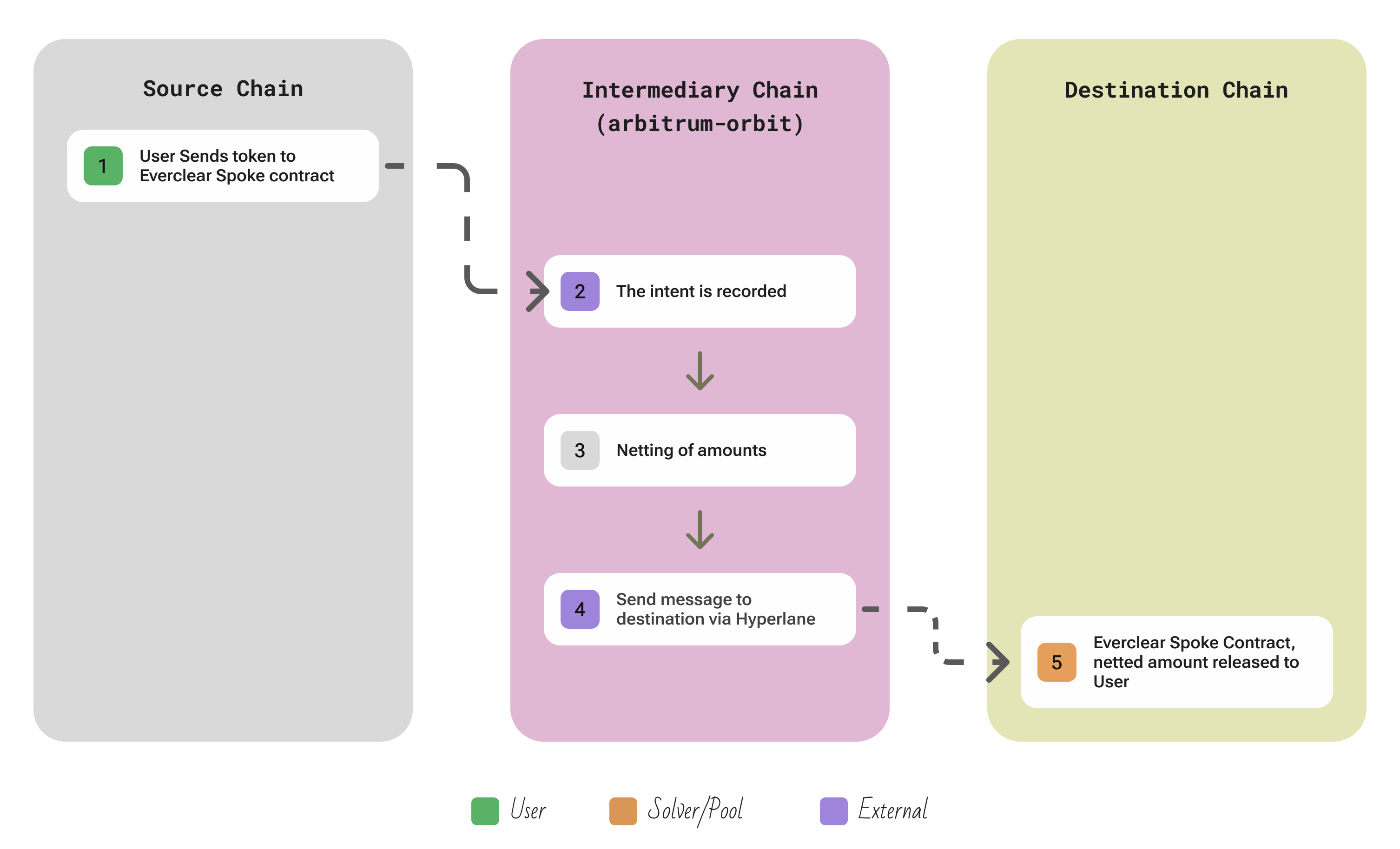

Everclear

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

A clearing layer that nets user intents and solver fills via Hyperlane, giving users instant payouts while balancing liquidity in a central hub.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; open Solvers pre-deposit liquidity and compete to fill it; a single Clearing Hub (Everclear’s own chain) that nets and settles intents; off-chain Relayers & Cartographer bots batch the queues and relay messages over Hyperlan. |

| Flow | The user generates a new Intent and submits it to the Spoke contract on the source chain, which locks the user’s funds and queues the intent → this intent is relayed to the Hub → The Hub chain’s Everclear module continuously matches incoming intents with available solver liquidity on destination chains (netting multiple intents if possible) → A Solver with available balance on the destination chain is selected (either via an auction or first-come competition) and fills the intent by immediately paying the user on the destination from its pre-deposited liquidity (through the Spoke on destination) → A corresponding Fill message is sent back to the Hub. The Hub, upon seeing both the intent and fill, “nets” them – effectively crediting the solver’s account and marking the intent as settled → Finally, a Settlement message is sent from the Hub to one of the Spoke contracts (whichever side needs to reconcile liquidity) to adjust the on-chain balances (e.g. transferring funds from the solver’s escrow to the user or vice versa). |

| Security | Solvers can only use funds they have prepaid into the Spoke contracts, and they receive payouts only through the Hub’s netting mechanism, so they cannot take user funds without delivering the service. Every settlement on the Hub requires matching intent and fill hashes, preventing mismatched or fraudulent fills. Cross-chain messages between Spokes and Hub are sent via Hyperlane (which itself has modular security), and if a message were tampered with or lost, the netting wouldn’t complete. Solvers are also typically required to stake a token (or be backed by stakers) and will be slashed if they fail to fulfill after claiming an intent, providing a financial guarantee. |

| Extendability | To add a new chain: deploy a standard Spoke contract on that chain and set up Hyperlane message passing to the Hub. Everclear is built to be permissionless – any chain can be integrated as a Spoke without needing approval, and any party can become a solver or relayer by depositing funds and (if required) staking, so long as they abide by the protocol’s rules |

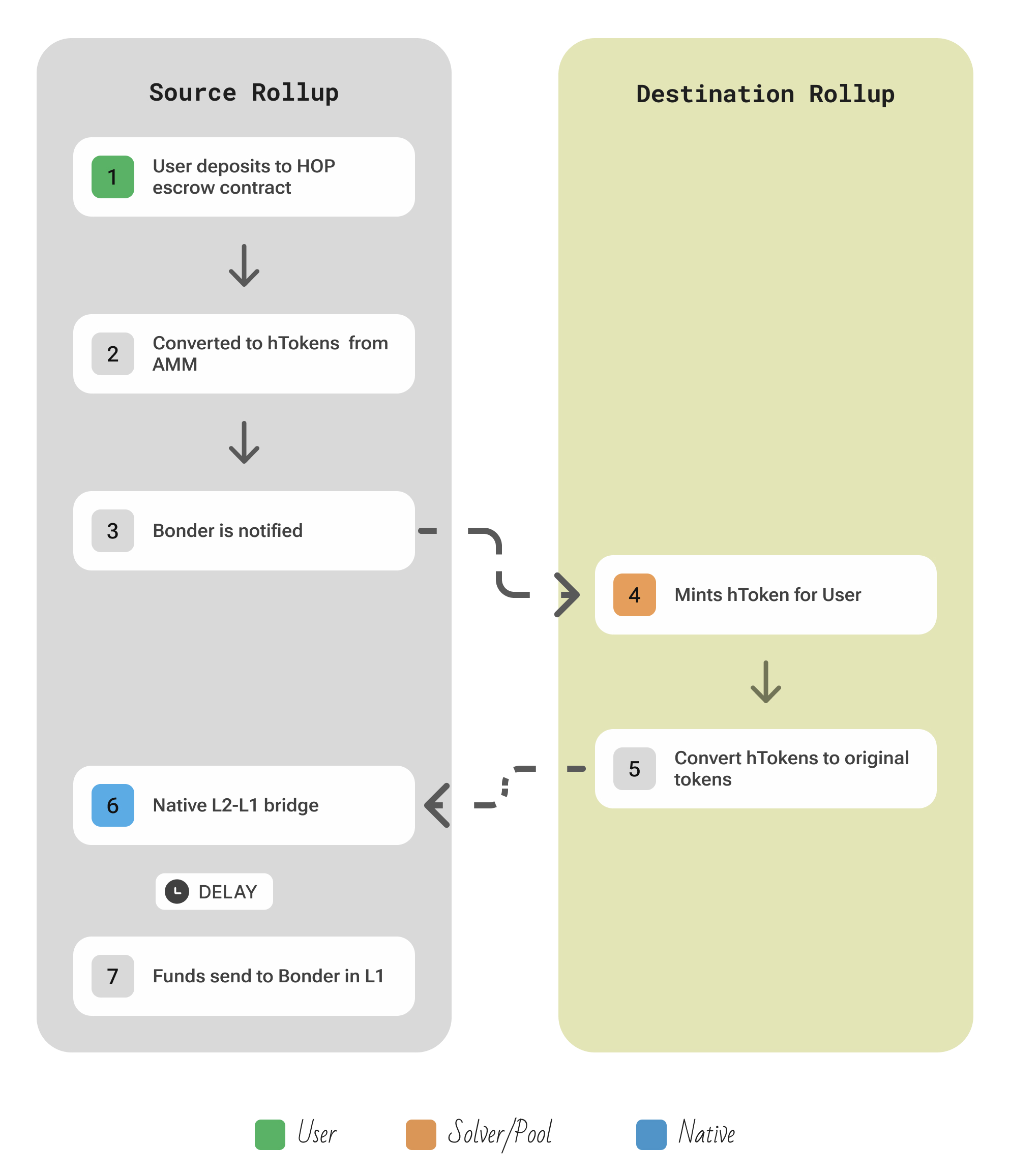

HOP

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

Rollup-centric bridge where bonders front hToken liquidity, AMMs swap to native assets, and the canonical bridges provide settlement

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; Bonders who front liquidity on the destination; AMM Liquidity Providers who facilitate swaps between the bridge’s hTokens and the native tokens on each chain |

| Flow | User deposits a token into the Hop bridge contract on the source rollup or L1 → this mints an intermediate hToken (a bridge IOU token) on the L2, or uses a canonical token if on L1 → A Bonder then swiftly sends the equivalent hTokens to the user on the destination chain and immediately swaps those hTokens for the local native asset via an AMM, giving the user the real token almost instantly. Meanwhile, the deposit is eventually confirmed on L1 (the canonical slow path); at that point, the bonder is reimbursed on the source chain (and the hTokens are burned) |

| Security | Hop adds no new external validators beyond the underlying chains. Bonders put up collateral and only earn fees if they honestly deliver funds and the transaction is later proven on L1. They cannot steal funds: if a bonder tries to cheat, the L1 proof will fail and they won’t be reimbursed. |

| Extendability | Primarily designed for Ethereum rollups. New L2 networks can be added by deploying Hop’s contracts and AMMs on them. |

Connext V2

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

A liquidity-network bridge that uses hashed-timelock atomic swaps and permissionless routers for fast, trust-minimized transfers across chains.

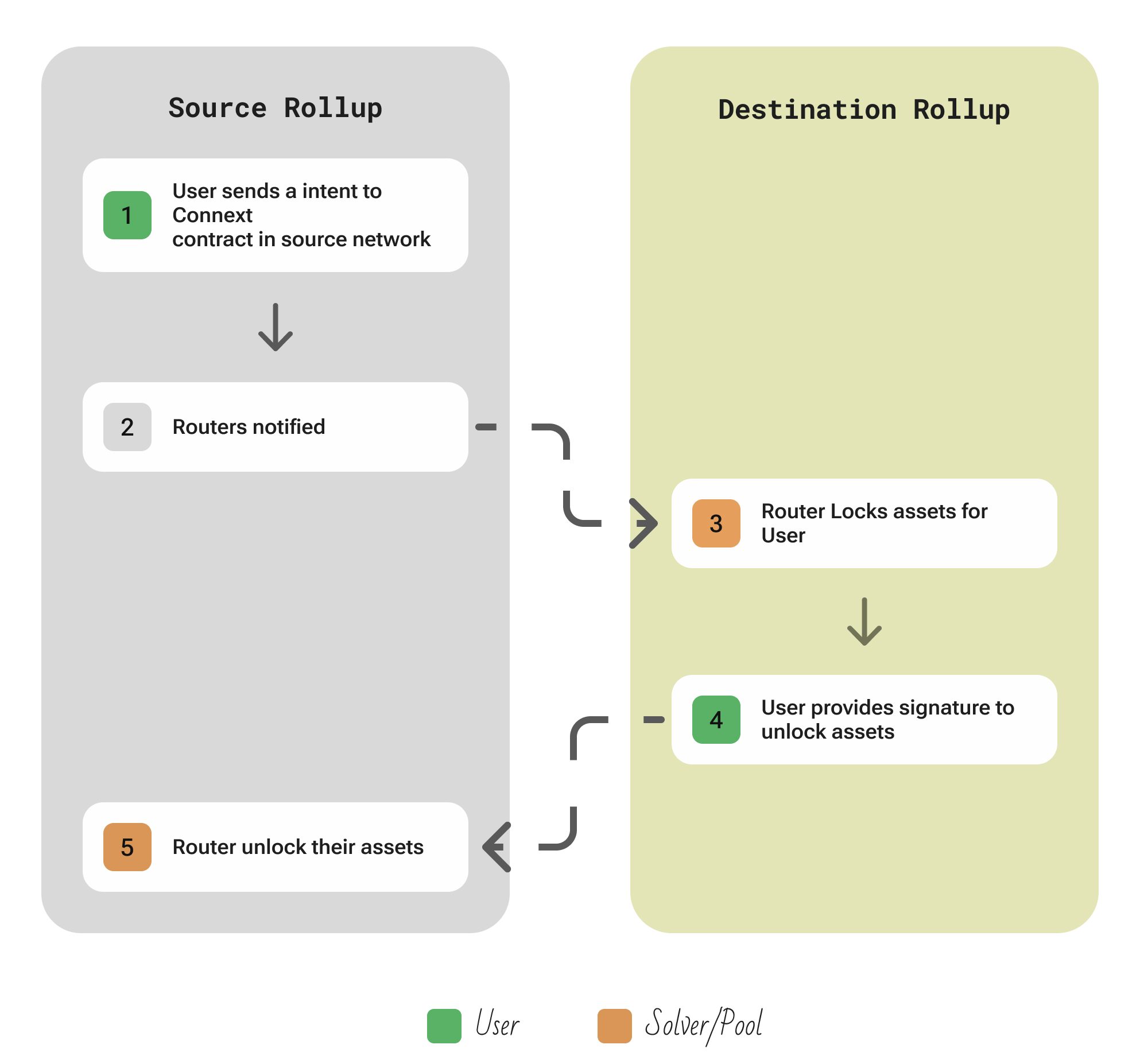

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; Routers (liquidity providers) who lock liquidity on destination chains; Relayers who pay destination gas fees for a small bonus |

| Flow | User invokes xcall on the Connext contract on the source chain, locking their tokens there → this emits a transfer intent → a Router listening to events then locks an equivalent amount of its own liquidity on the destination chain for the user, effectively fronting the transfer. The user (or relayer) then provides a cryptographic proof of the original lock to the destination contract (or the router presents a signed fulfillment from the user) → upon proof, the user receives the tokens on the destination, and the Router is reimbursed on the source chain (unlocking the initially locked funds back to the router) |

| Security | Connext uses a classic two-phase HTLC model: assets are escrowed on both chains and only released if a valid secret/key is provided (or a proper off-chain signature and proof). There is no third-party consensus mechanism – security reduces to the guarantee that either both escrows complete or both refund. In other words, it’s as secure as the source and destination blockchains themselves. |

| Extendability | The protocol is general-purpose and works on any EVM-compatible chain out-of-the-box, and could be extended to non-EVM with compatible contracts. Anyone can deploy the Connext contracts to a new chain and become a router there. |

Note: Connext V2 has evolved into Everclear. The original Connext V2 faced challenges with rebalancing issues and solver liveness, and was limited to EVM chains. The team has since launched Everclear as their next-generation clearing layer solution.

Across

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

An optimistic bridge where relayers front funds instantly and UMA’s oracle later settles.

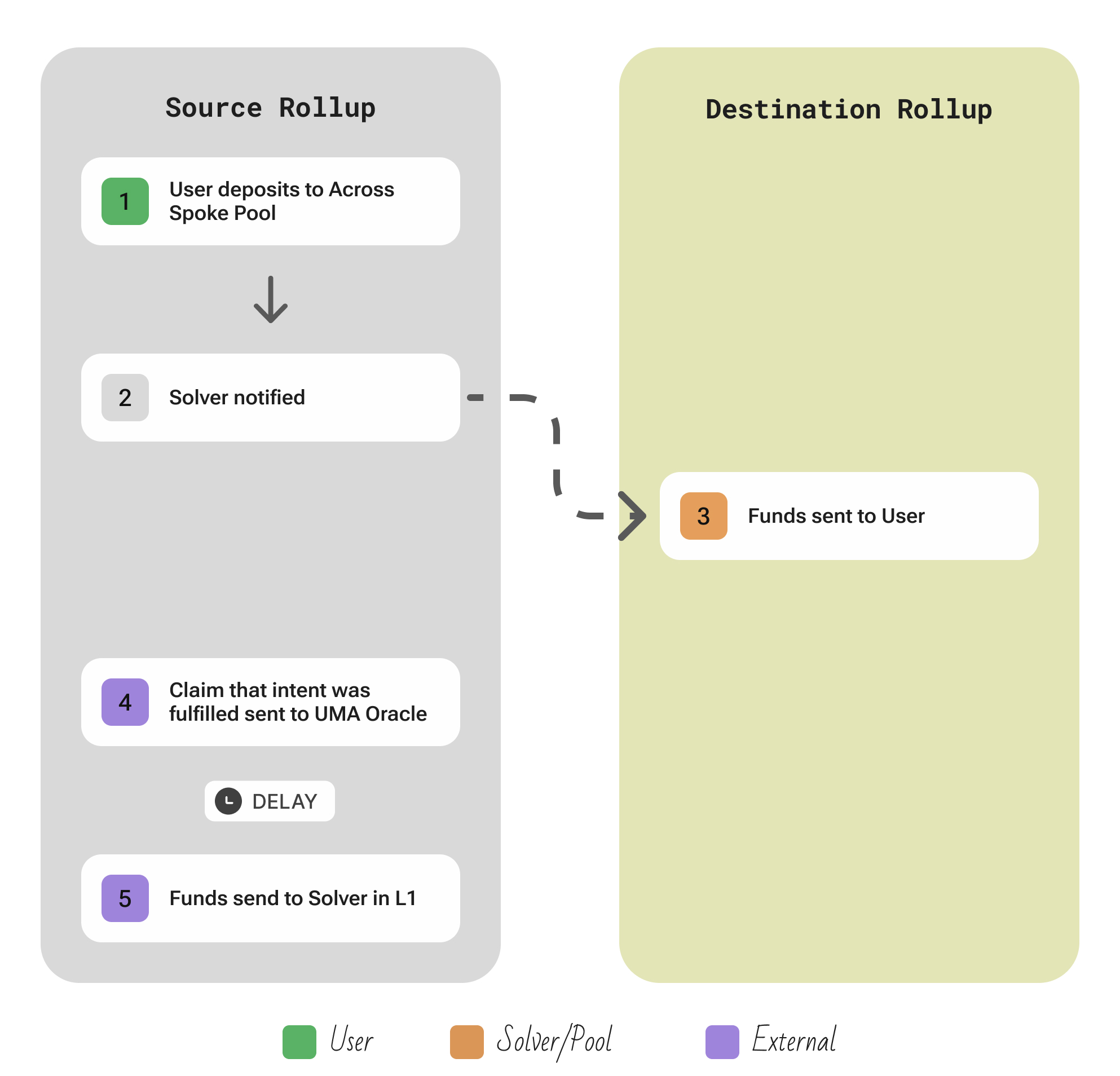

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; an open set of Relayers (Solvers) who compete to fulfill transfers; UMA’s Optimistic Oracle voters who arbitrate claims, and liquidity providers in the Across Hub Pool on Ethereum |

| Flow | User deposits assets into a Spoke Pool contract on the source chain → a fast Relayer (solver) immediately sends the equivalent funds to the user on the destination chain out of the solver’s own liquidity (so the user gets funds “instantly”) → that solver then submits a claim to UMA’s optimistic oracle asserting that it bridged the funds correctly. After a configurable challenge period, if the claim is not disputed by any watcher, it is accepted. Then the solver is reimbursed from the protocol’s Hub Pool liquidity on Ethereum. |

| Security | Across relies on optimistic security: any incorrect claim can be disputed by the oracle’s participants within the challenge window, in which case the solver’s posted bond is slashed. The bond is provided along with the transaction which fulfilled the user’s intent in the destination chain. |

| Extendability | The bridge logic itself can work on any chain where UMA’s optimistic oracle is available to verify claims. In practice, UMA (and Across) currently support only EVM chains. |

Anyone can technically run a relayer, but the majority of order flow is routed to exclusive Relayers, which the team has to confirm/allow to become a relayer.

Synapse

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

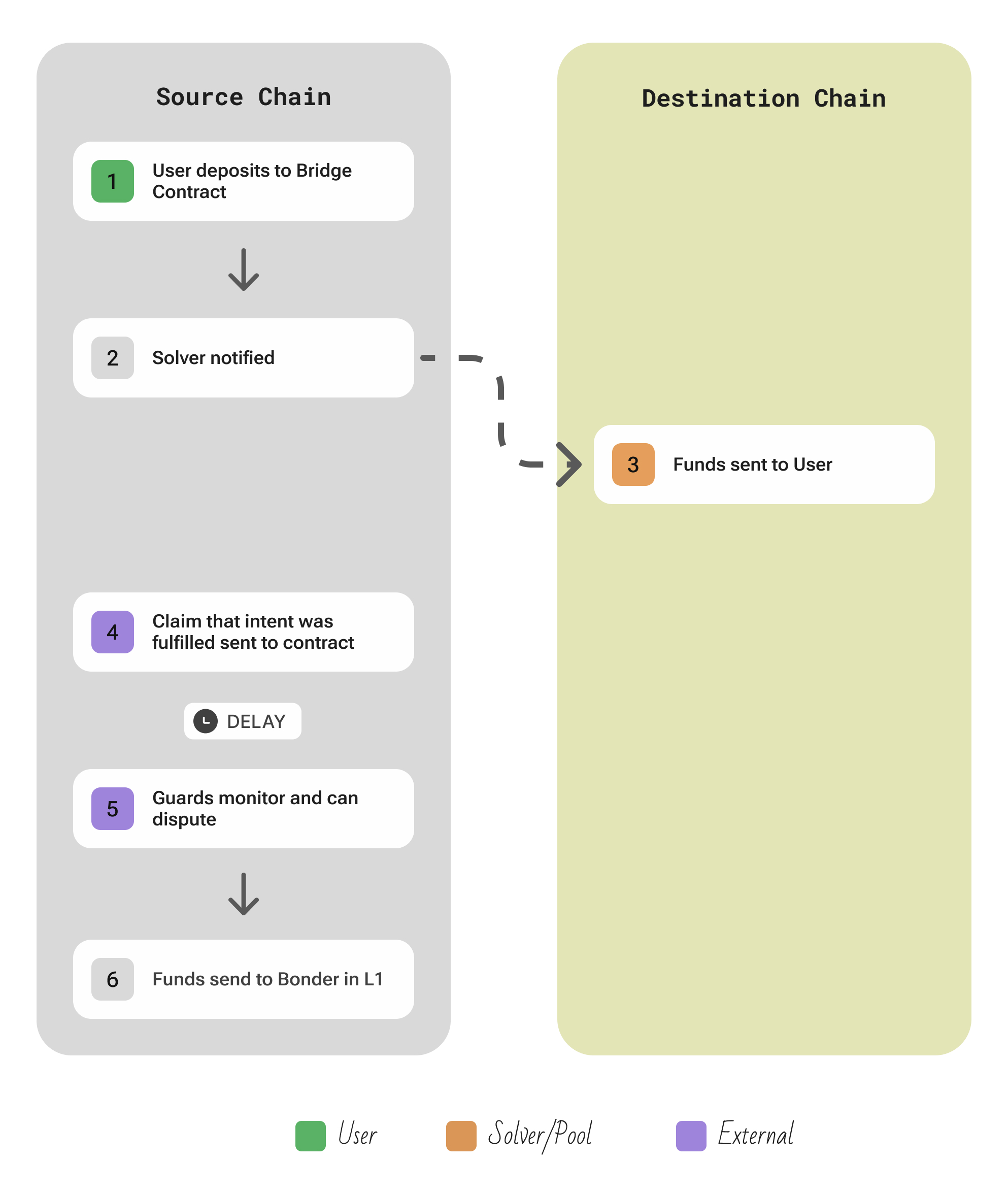

Optimistic bridge where collateral-posted relayers fulfill transfers immediately and guards can dispute within a challenge window.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; off-chain Relayers who fulfill user transfers immediately; Guards who watch for fraud during a dispute window; LPs who fund the pools used for fast swaps |

| Flow | The user initiates a transfer via the Synapse Router contract on the source chain → Immediately, a Synapse Relayer on the destination chain executes a corresponding transaction, providing the user with the requested tokens almost instantly out of Synapse’s liquidity pool. In the background, the relayer then submits a prove transaction on the origin chain, attesting to what it did on the destination → this starts an optimistic challenge window during which the action can be reviewed. Guard nodes (anyone can run a guard) monitor all cross-chain actions; if a guard detects that the relayer’s output was illegitimate (e.g., it claimed more tokens than were actually locked on source, or a different user’s funds), the guard can dispute the proof within the window. If the transfer goes undisputed until the window expires, it is considered valid. At that point, the relayer is allowed to claim the originally locked tokens (or equivalent) from the Synapse contract on the source chain as reimbursement. |

| Security | Synapse uses an optimistic security model: it assumes transfers are honest by default but relies on at least one honest guard to challenge any malicious or invalid cross-chain transaction. Relayers must put up collateral and they do not get paid until the dispute period passes, meaning they stand to lose money if they cheat. |

| Extendability | Adding a new chain involves deploying the Synapse bridge contracts there and including that chain’s light-client verification in the proving mechanism. Since relayers and guards are permissionless roles, they can simply start supporting the new chain by running nodes and watching its events – no explicit approval needed. |

Meson

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

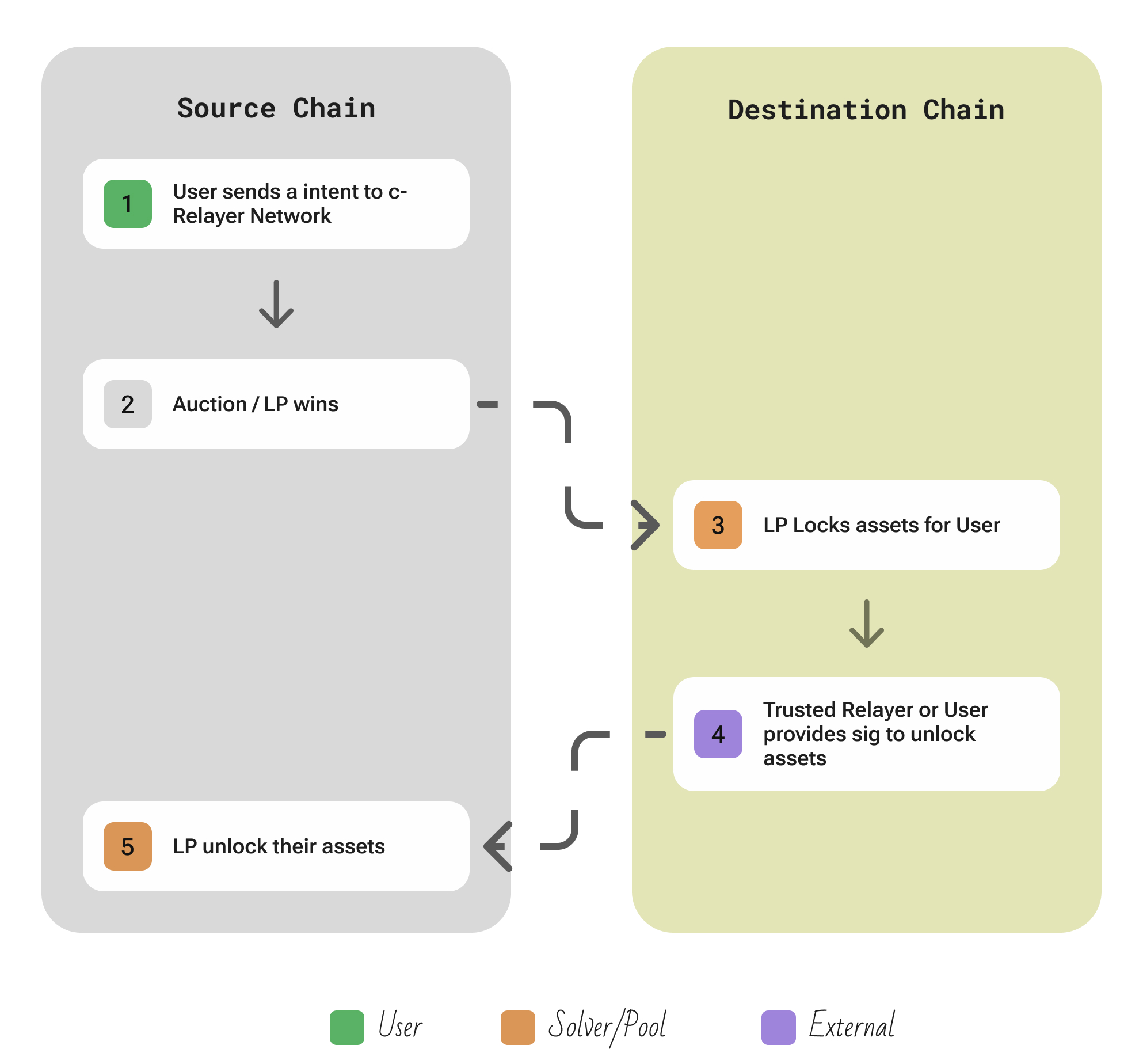

Atomic-Swap HTLC network allowing LPs match stable-coin transfers between any chains with no validators and 3rd parties

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; competitive Liquidity Providers (LPs) commits to swaps; a p2p / optional c-Relayer network just broadcasts messages (never holds funds); optional Trusted Verifiers can co-sign for absent users |

| Flow | the user signs an off-chain order with details of the swap (amount, source, destination) and a secret hash. This order is gossiped to all LPs via relayers. → the first willing LP for that pair/trade bonds the order on the source chain by locking an equivalent amount of the user’s token in a Meson smart contract (escrow) on Chain A → this “bond” claims the right to execute the swap → that same LP simultaneously locks its own liquidity of the target token on Chain B in a corresponding escrow contract → now two HTLC escrows are in place – one holding user’s funds on A, one holding LP’s funds on B – both secured by the same hash and with timeouts. The user (or their designated trusted verifier) then reveals the secret preimage by signing a release transaction on the destination chain → using this secret, anyone can call the release on Chain B, giving the user the LP’s locked funds (the desired token on B) → the LP then uses the disclosed secret to unlock the escrow on Chain A, retrieving the user’s tokens (plus a fee) on Chain A |

| Security | Meson’s design is a pure atomic swap via HTLC: either both escrows are claimed with the same secret, or both expire and funds revert, which means neither party can steal from the other. There are no middlemen holding funds; the smart contracts on each chain enforce the hashlock/timelock. |

| Extendability | Meson’s contracts are lightweight and independent on each chain. To add a new chain, one simply deploys the Meson escrow contract there. Because swaps are peer-to-peer between LPs and users, any new chain automatically can swap with all existing ones as long as some LP provides liquidity for that route. |

I use this bridge really rarely, but I thought it’s good to mention them as they use Atomic Swap workflow as well. Their approach with Trusted verifier is default in their dApp so basically you trust someone not to steal your funds (if they collude with LP they can steal) which I am not a fan of and it completely demolishes the beauty of Atomic Swaps. Again this is a decision to stay competitive in the market, because as you could see with pure atomic swaps User has to do 2 steps which no one is a fan of. As everyone thinks that all problems with crypto is UX.

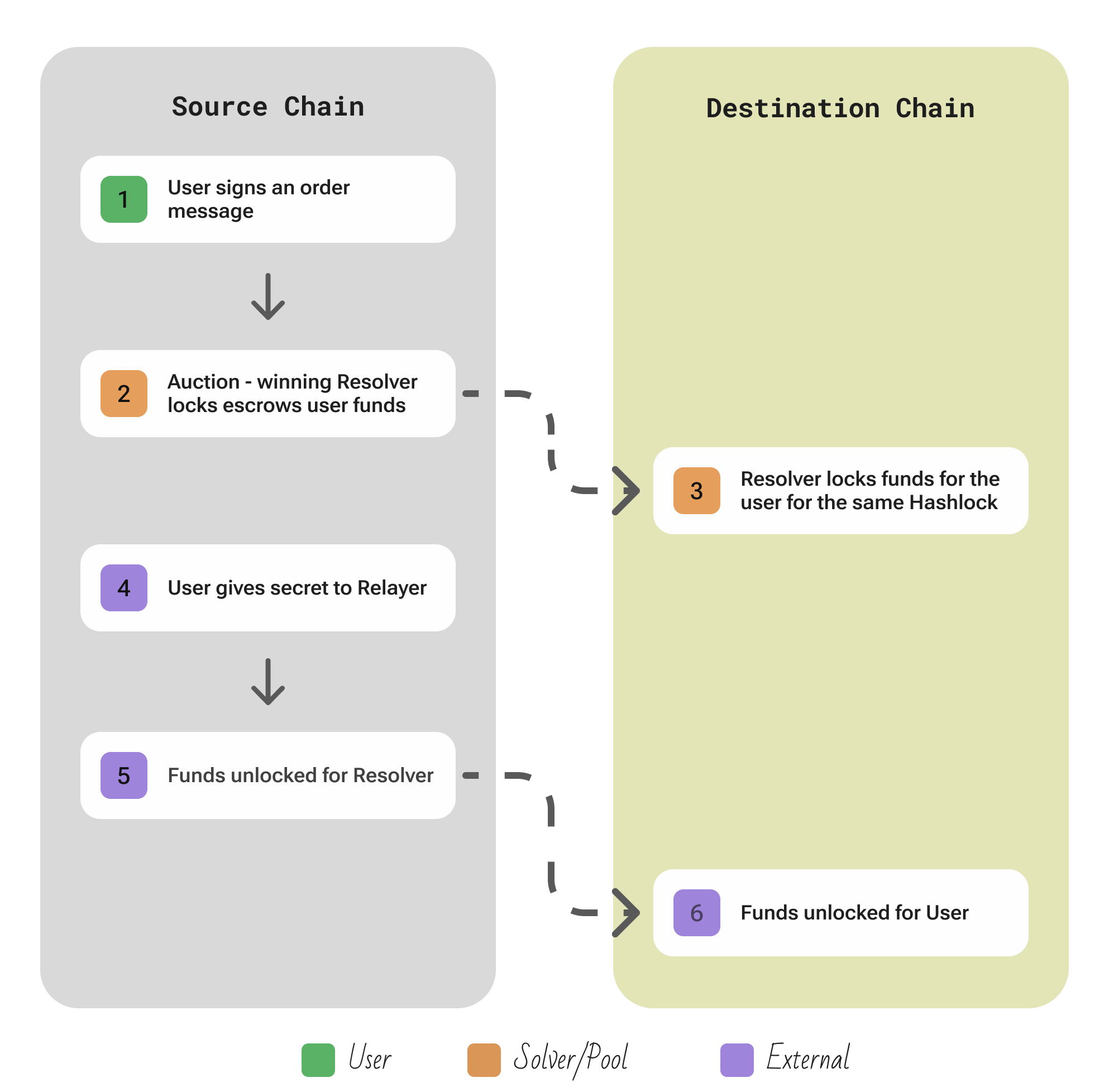

1inch Fusion+

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

Dutch-auction HTLC swaps filled by staked resolvers who atomically lock and release funds on both chains.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; competing Resolvers (KYC’d market-makers that pre-fund liquidity and stake 1INCH for “Unicorn Power”) race to fill it; a Relayer/Auction broadcasts orders and later reveals the secret; on-chain Executor that posts the final tx and receives a small tip. |

| Flow | The user submits a swap intent via the 1inch UI, specifying source asset, destination asset, amount, and a duration for the auction. This order is off-chain but signed by the user → It enters a Dutch auction off-chain, where Resolvers see it and over time the price offered to Resolvers becomes more favorable → when a Resolver decides to fill the order, here’s what happens: The Resolver calls the 1inch Fusion smart contracts on each chain: locking the user’s tokens (which the resolver may pull via a signed permit or the user’s prior approval) into an HTLC on source, and locking their own tokens into a corresponding HTLC on destination. Both escrows use the same hashlock → Once both escrows are in place and the auction finality time has passed, the 1inch Relayer service reveals the secret (the preimage for the hashlock) publicly → with the secret now revealed, the Resolver can unlock the source-chain escrow, claiming the user’s original tokens (this is the resolver’s payment). Likewise, the user (or the executor on their behalf) uses the secret to unlock the destination escrow, releasing the output tokens to the user. |

| Security | Fusion+ operates via hashed timelock contracts on each chain, achieving true atomic swaps (either both legs complete or both revert). As such, neither the user nor resolver can cheat – the user only gets the output if the resolver gets the input and vice versa. Resolvers do require the user to sign a permit or give token approval on the source chain (so the resolver can move the user’s tokens into escrow when they fill the order), but this permit is used strictly within the atomic swap and cannot be abused outside the specific order. The staked 1INCH and KYC requirements for resolvers add an extra layer of security: resolvers have reputation and funds at stake, so malicious behavior would result in slashing of their Unicorn Power (and likely legal action since they are identified) |

| Extendability | 1inch Fusion+ is readily extensible to new chains since it requires only the deployment of the standard Fusion escrow contracts on that chain. Once that’s done, any resolver that has or can obtain liquidity on that chain can start filling cross-chain orders involving that chain. |

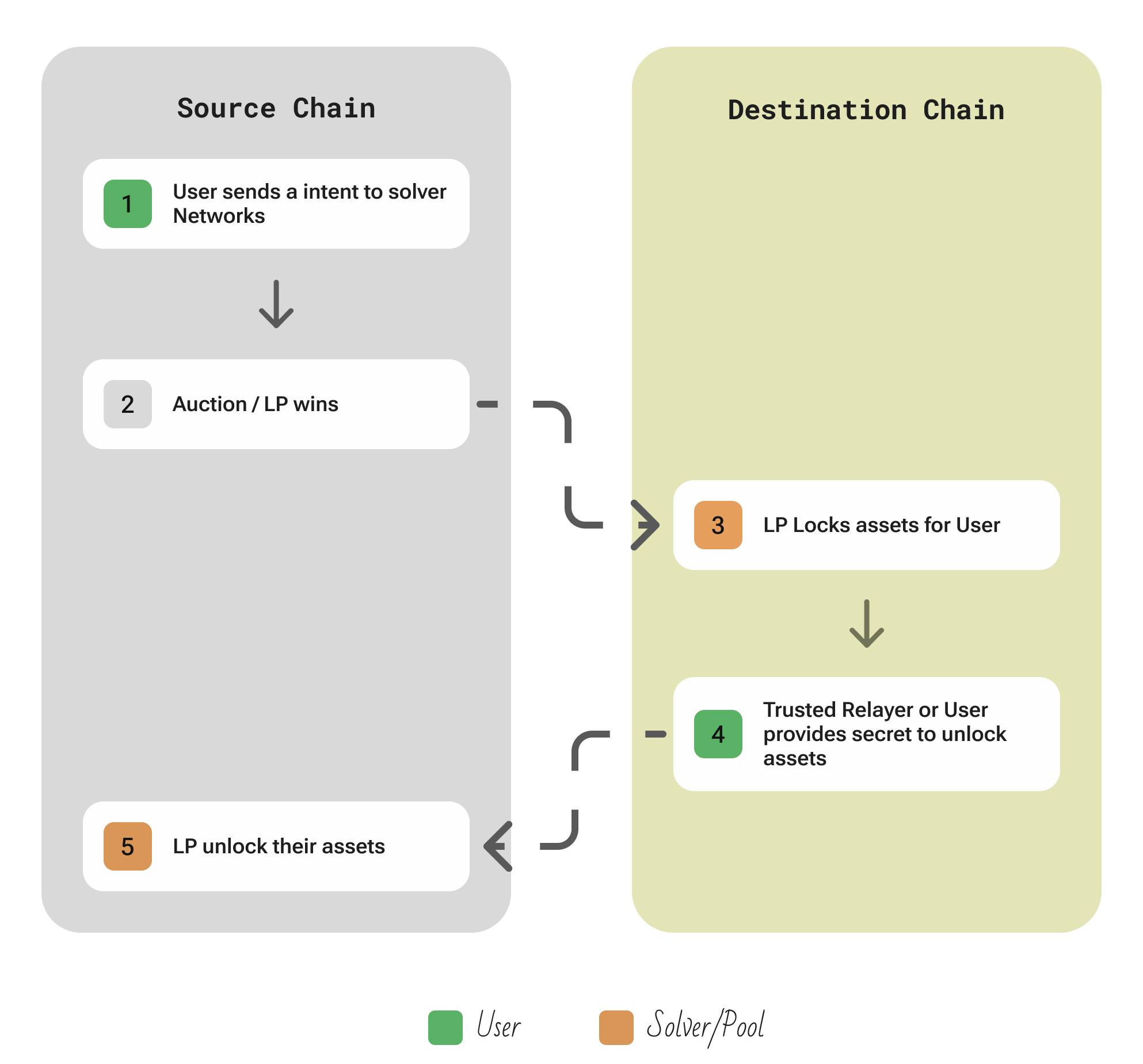

Garden Finance

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

Intent-based HTLC network where staked solvers compete to fill swaps and face slashing if they fail to execute correctly.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; competitive Solvers (LPs that pre-deposit liquidity and stake SEED) picked by a decentralized order-book; optional Relayers just broadcast signed messages; Stakers back solvers and get slashed on failure. |

| Flow | The user submits a cross-chain swap intent through an interface or by signing a transaction, which is posted to a decentralized intent marketplace monitored by solvers. Solvers compete to fill the intent, and once one is selected, the user is instructed to deposit the source asset into an HTLC contract. Simultaneously, the solver locks the destination asset in a corresponding HTLC using the same hash. When both escrows are active, the user reveals the preimage to claim the destination asset, which also enables the solver to redeem the source asset. If either party fails to act in time, the timelocks ensure all funds are safely refunded, and the solver may be slashed for non-fulfillment, ensuring reliability and accountability. |

| Security | Garden Finance employs hashed timelock contracts just like classic atomic swaps, so the fundamental security is that no one can lose funds: either both transfers happen or both refund. On top of that, Garden introduces solver staking and slashing via the SEED token: if a solver fails or cheats (for instance, tries to cancel after seeing the price move), they can be financially punished, and their backers lose stake. |

| Extendability | To extend to a new chain, it needs the standard HTLC contracts deployed on that chain and for solvers to have liquidity there. Since it’s intent-based, every new chain instantly interoperates with all others because solvers can route between any two supported domains. |

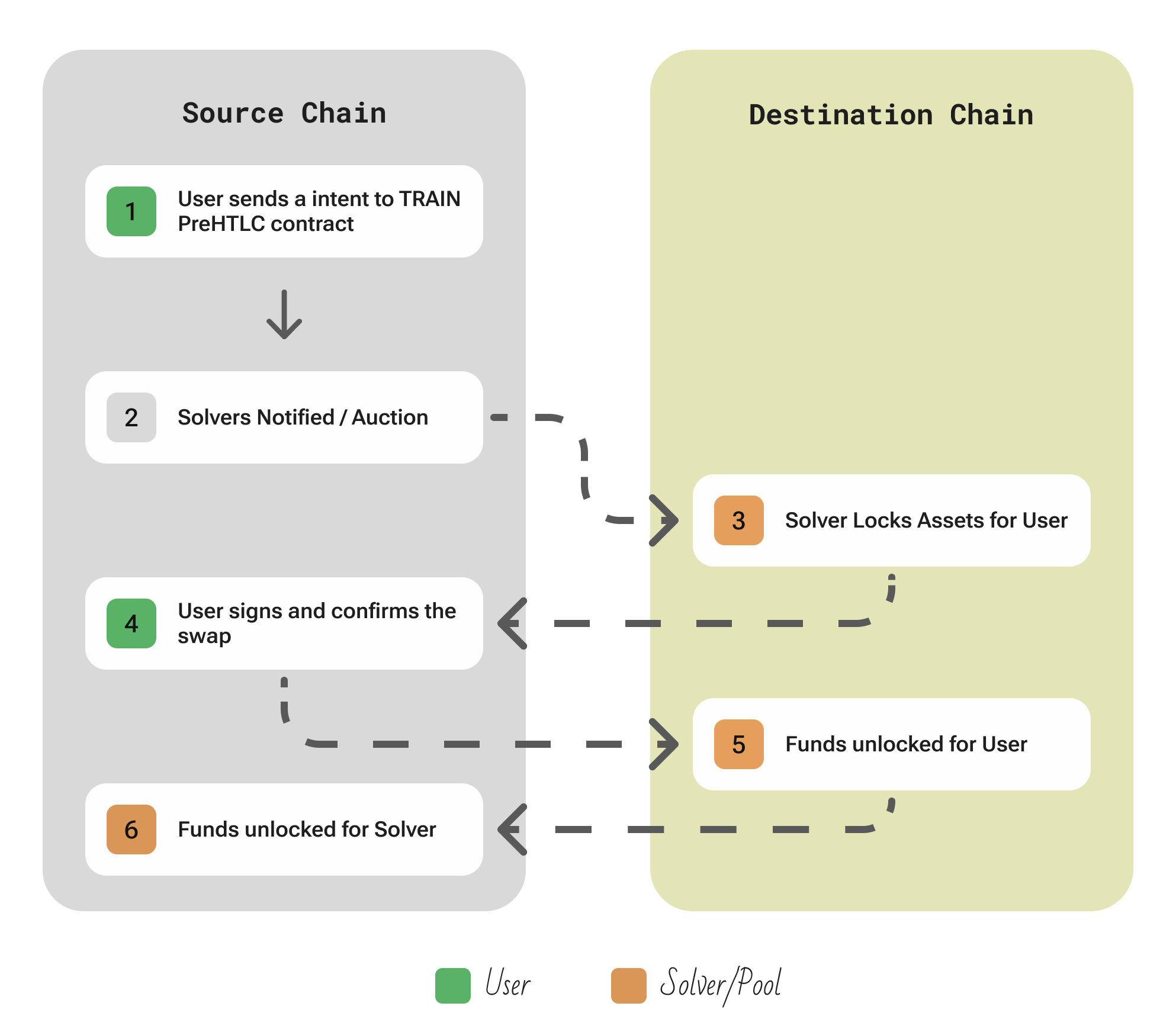

TRAIN

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

A permissionless cross-chain swaps protocol that uses atomic PreHTLC escrows and competitive solver auctions to enable trustless asset swaps between chains

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; Solvers (liquidity providers) listed in the on-chain Discovery registry |

| Flow | The user initiates a cross-chain swap by submitting an intent to the TRAIN contract on the source chain, which locks their funds in a PreHTLC escrow. This intent is broadcast and picked up by solvers, who compete to fulfill it via an off-chain auction or algorithm. The selected solver locks equivalent funds on the destination chain. Once both escrows are active, the user transmits the hash of the destination lock to the source chain contract to confirm readiness. The solver then reveals the secret to release the escrowed funds on the destination chain, and claim their funds in the source chain. If either party fails to proceed, both sides can reclaim their funds after the timeout. |

| Security | TRAIN is built on pure atomic swap mechanics using HTLCs: either both parties fulfill the swap or both get refunded, eliminating unilateral risk. |

| Extendability | Deploying TRAIN on a new chain automatically connects it to all other TRAIN-supported networks, because intents can be created on that chain and any solver can fulfill them by locking on another chain. There’s no centralized setup per chain – solvers self-register permissionlessly via the on-chain Discovery, and any chain’s contract simply uses the same standardized HTLC interface. This means the system scales completely permissionlessly: if a chain (EVM or non-EVM) supports hashlocks and timelocks, it can be added by deploying the standard contracts, and solvers will start servicing it as soon as there’s demand |

I am the co-founder of this protocol. Take this with a bunch of salt.

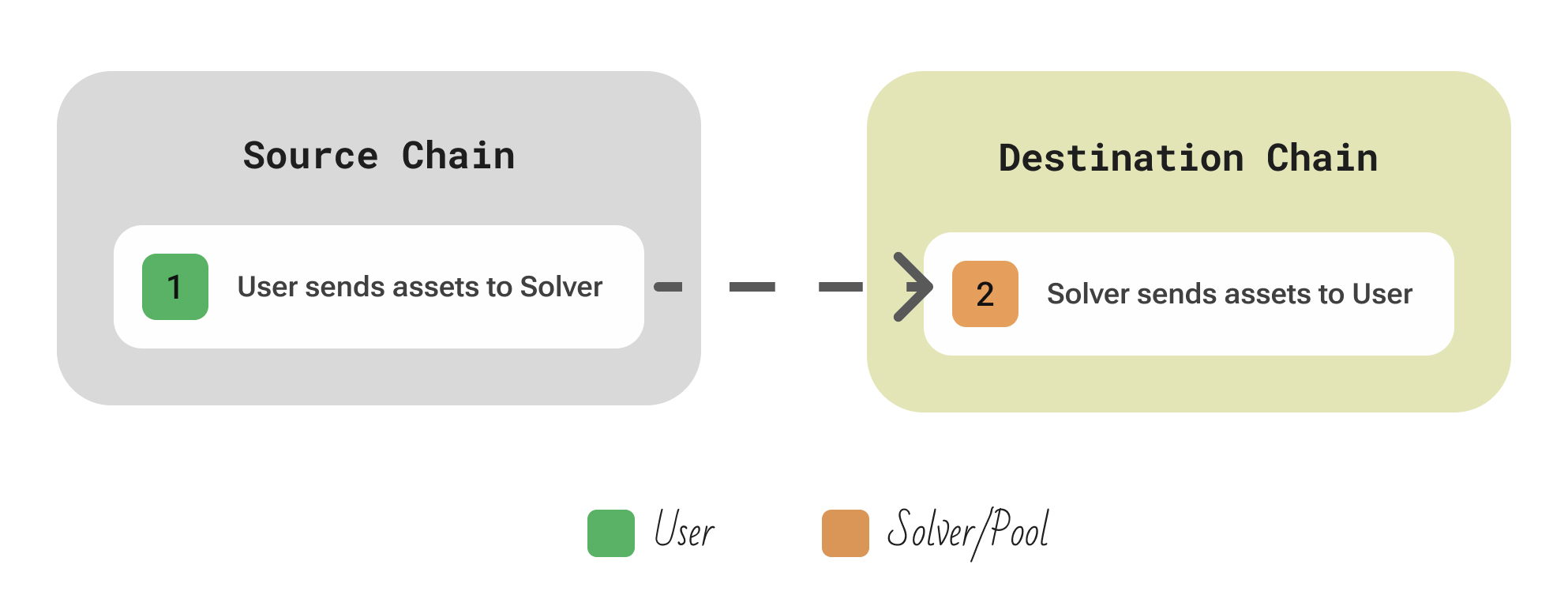

Centralized Bridges

Examples: Layerswap | Relay | Orbiter

A single trusted party (the solver) receives user funds on the source chain and transfers equivalent assets from its own inventory on the destination chain

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; Centralized Solver |

| Flow | The user requests a transfer quote from the service (specifying source chain/asset and destination) → the service provides a rate/fee. The user then sends their tokens directly to the service’s address on the source chain → once the service detects the deposit (or has custody of the user’s funds), it instantly transfers the target asset from its own liquidity on the destination chain to the user’s address. |

| Security | No on-chain security guarantees beyond the service’s honesty and solvency – this is effectively a custodial transfer. |

| Extendability | Since the service uses its own off-chain accounts and liquidity, it can integrate any chain or asset it chooses, as long as the operators are willing to support it. No smart contracts are needed on the chains (aside from perhaps a deposit address); the scalability is limited only by the service’s operational capacity. |

Oh boy. These players are kind of disruptive in this space. With a centralized design, it is WAY easier to operate a solver, much more straightforward.

CCTP

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

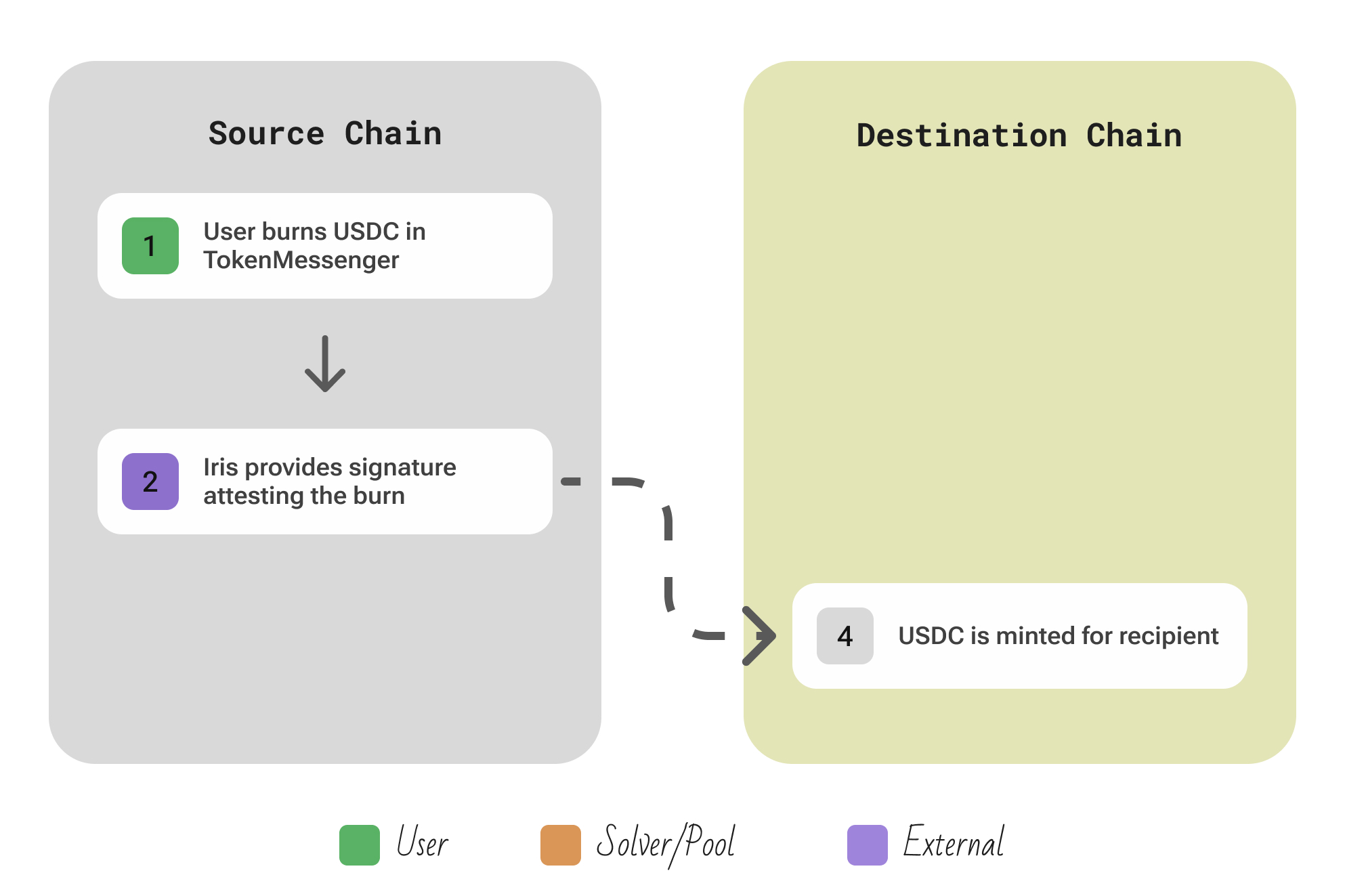

Circle’s burn-and-mint bridge that lets native USDC move across chains by burning on the source chain and minting on the destination

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User; Off-chain Circle Attestation Service (Iris); any Relayer for transmiting signatures |

| Flow | User calls depositForBurn() on the source-chain TokenMessenger, burning native USDC and emitting a message ID → Iris detects the burn once the block meets the chosen finality threshold (hard-finality for Standard transfers, soft-finality for Fast transfers in CCTP V2) and returns a signed attestation. → Any relayer submits the attestation to the destination chain’s MessageTransmitter via receiveMessageWithAttestation(), which verifies the signatures and mints the same amount of native USDC to the recipient. |

| Security | CCTP provides cryptographic security through Circle’s attestation service using threshold signatures. Tokens are burned on the source chain and minted on the destination only with valid attestations from Circle’s trusted nodes. While centralized, it’s not custodial - Circle never holds user funds, and the burn-and-mint mechanism ensures 1:1 backing across chains. |

| Extendability | (i) Adding a new chain requires (i) Circle issuing native USDC there, (ii) deploying the two contracts, and (iii) Iris starting to watch that chain—so expansion is fast but centrally coordinated by Circle. |

LayerZero

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

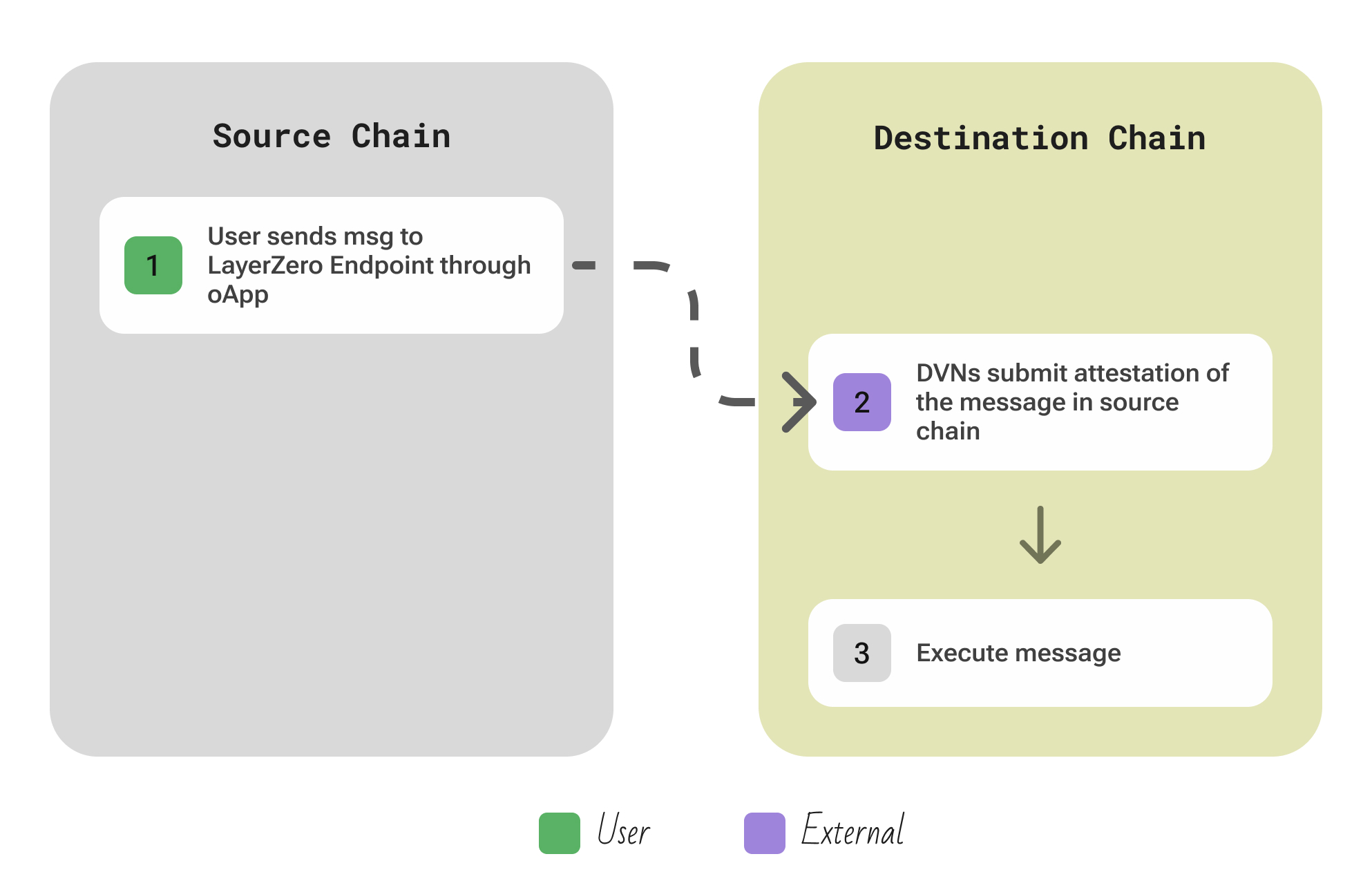

Modular messaging layer that uses configurable decentralized verifier networks plus executors to deliver payloads.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User/App; Configurable DVNs (Decentralized Verifier Networks) that attest each payloadHash, off-chain Executor that pays gas and calls the destination contract |

| Flow | The user’s contract calls lzSend(payload, dstChain, ...) on the source Endpoint → for each DVN configured for that app, a node (or set of nodes) in that DVN independently fetches the message and verifies the source chain state (e.g., it may retrieve a block header via a light client or use an oracle service) → These attestations are delivered to the destination chain’s Endpoint contract, typically by the DVN operators themselves → once a specified threshold of attestations is received as defined by the app’s security policy, the message is considered verified → At that point, an Executor calls the Endpoint’s deliver() to assemble the attestations and trigger the target contract’s lzReceive() on the destination chain. |

| Security | LayerZero’s security is modular and customizable. A message is only executed if the configured DVN quorum(s) all attest to the same payload hash. Apps can choose a mix: e.g., require a signature from a community-run multisig and a proof from a ZK verifier. No single entity can forge data because it wouldn’t satisfy the required threshold. Additionally, app developers can lock in their DVN configuration on-chain so that even they cannot change it later. |

| Extendability | Adding a new chain to LayerZero is as easy as deploying the Endpoint contract there (which any party can do, subject to LayerZero governance approval for now). The protocol doesn’t require every verifier to support every chain – new DVNs/relayers can elect to support the chains they care about. Because each application chooses its own security configuration, connecting a new chain does not force a global trust change; apps on that chain can use existing DVNs or new ones. In practice, LayerZero has rapidly expanded across dozens of chains (including Cosmos chains, Aptos/Sui, etc.), since the endpoint is lightweight. The Executors and DVNs are permissionless – anyone can run a DVN or an executor service for a chain. |

Hyperlane

Links: Website | Twitter | GitHub

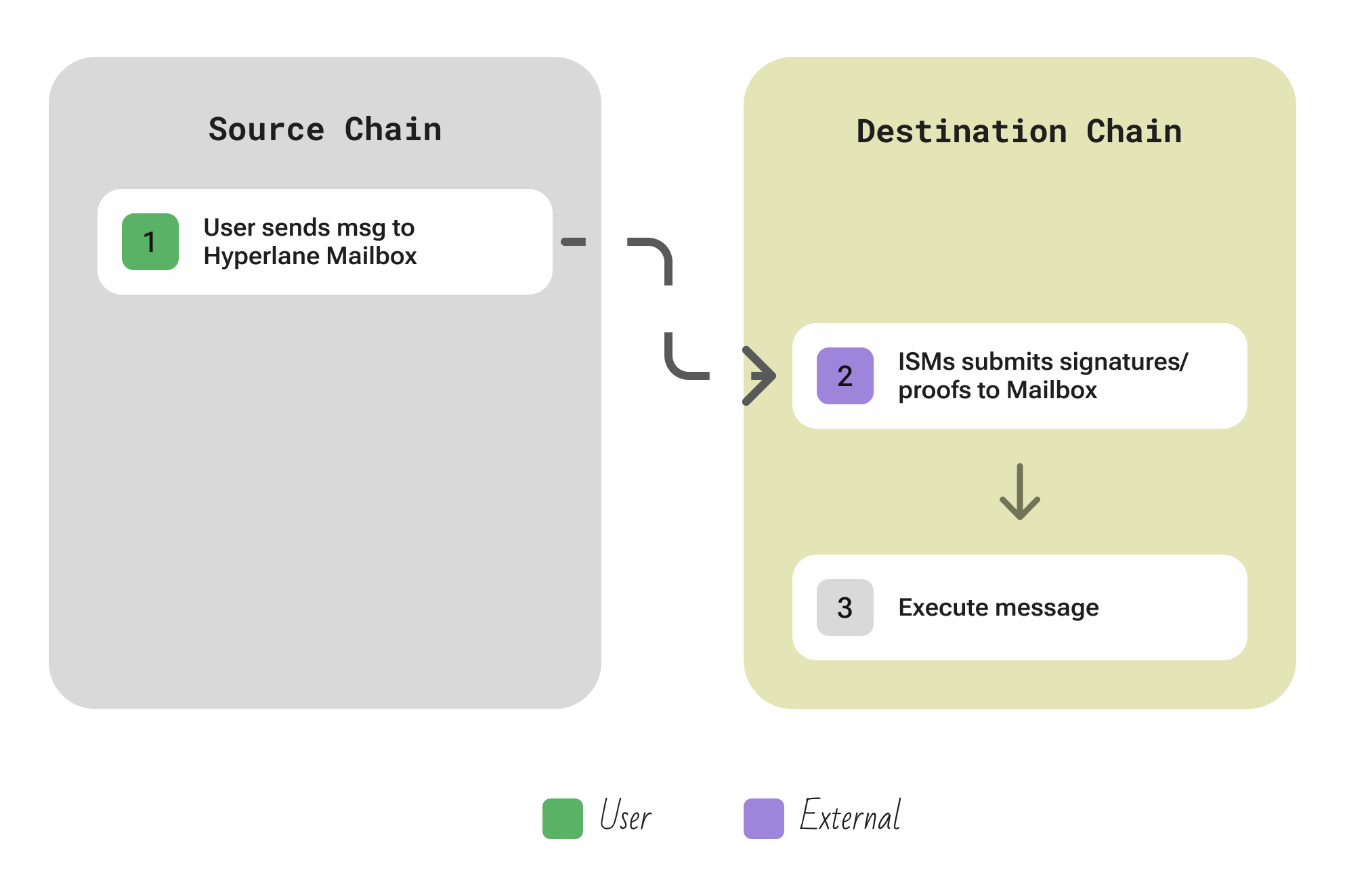

“Choose-your-own-security” mailboxes where each app picks its interchain security module—multisig, staking, ZK, or custom—for permissionless messaging.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Participants | User/App; Configurable ISMs (Configurable Interchain Security Modules) that validate incoming messages; off-chain Relayers that carry messages from source to destination. |

| Flow | A user’s contract calls dispatch(message, destChain) on the local Mailbox contract, which logs the message → an off-chain Relayer picks up the message and the accompanying proof (Merkle path) and submits a transaction to the Mailbox on the destination chain calling deliver(message, proof) → the destination Mailbox then invokes the application’s chosen ISM module to verify the proof and the origin of the message → if the ISM’s verification passes (i.e., the message is proven authentic according to the app’s security rules), the Mailbox contract calls the specified handler function on the destination contract, delivering the message payload. |

| Security | Hyperlane offers configurable security per message. Each ISM can enforce a different trust model. If a message passes the ISM, it means it met the exact criteria the app set (no weaker assumption). If a validator tries to approve a fraudulent message, their stake can be slashed (when using the default or any stake-based ISM). If using an external light client ISM, a bad proof is simply invalid. One honest party (in a multi-ISM config) can veto a bad message by not signing or by detecting a bad proof. |

| Extendability | Hyperlane is permissionless by design: anyone can deploy the Mailbox contract to a new chain and connect it to the Hyperlane framework. There’s no requirement for a global validator set to support a chain – if a chain isn’t supported by the default ISM validators, a project could deploy their own ISM (even a simple multisig of their own validators or a custom light client) on that chain. Relayers are also permissionless; any relayer can carry messages (they are trust-minimal as they don’t verify, just pass along data) |

–

As we get here, to quickly recap: interop is at really early stages. All the solutions come with gigantic tradeoffs, often ones that are not easily spottable on the surface, some of them are intentionally misleading, some of them actually have a good path forward that can benefit the whole crypto ecosystem. Whatever it is, we are right now in a big experimental stage, where we will see what kind of projects can start thriving. I almost think that whatever it was possible to try and explore has been done; the question is how the existing solutions and the crypto ecosystem will grow generally.